Today at 83, Ed Mickelson is a silver-haired Cary Grant type living out his happy life in St. Louis, Missouri. Yesterday at 27, he collected the last run batted in recorded in St. Louis Browns history. He did it in a 2-1 losing cause against the Chicago White Sox on the last day of the 1953 season at old Sportsman’s Park. I wrote a parody to commemorate the event, once upon a time. That signature RBI wasn’t the only thing that Ed ever did in baseball, but it is the thing he wants to be remembered for having done as a member of the Browns’ far from legendary last club on earth back in 1953. The next season, the franchise moved to Baltimore and hatched upon the scene as the Orioles.

In 2007, Ed Mickelson personally wrote his own story and published it through McFarland’s. Still available through Amazon, the Mickelson biography is entitled “Out of the Park: Memoir of a Minor League Baseball All Star.” It’s well written and a good read, detailing Mickelson’s eleven season career (1947-57). He started with Decatur and ended up with Portland, achieving a lifetime minor league batting average of .316 and 108 home runs in 1,089 minor league games played. Ed even went 3 for 9 as a Houston Buff in 1952 before being reassigned by the parent Cardinals club to Rochester.

Mickelson also played 18 games total in the major leagues for the 1950 St. Louis Cardinals, the 1953 St. Louis Browns, and the 1957 Chicago Cubs. That record RBI single that scored Johnny Groth from second base in 1953 also was one of only three RBI that Ed managed in his brief major league career. His MLB average of .089 helps to explain his limited action beyond the minor leagues.

Ed Mickelson is one of the nicest people you could ever meet. He’s a bright guy who looks the part of his current role as an aging gracefully first baseman. The BR/TR, 6’3″ and still lanky guy could not better look the part if he tried.

Mickelson compiled a number of honors for his minor league play over the years, but that’s the stuff of Ed’s story in the book. Just one peek here: Ed Mickelson is also notably proud of the fact that he got his first major league hit in the form of a single off the great Warren Spahn back in 1950. I definitely remember Ed’s short 1952 stay with the Buffs too, but the Cardinals didn’t leave him here long enough to do that sad Buff team much good.

In honor of Ed Mickelson’s last RBI in St. Louis Browns history, here’s that parody I wrote years ago in all their honors:

The Lost Hurrah: September 27, 1953

Chicago White Sox 2 – St. Louis Browns 1.

(A respectful parody of “Casey At The Bat” by Ernest L. Thayer in application to the last game ever played by our beloved St. Louis Browns.)

by Bill McCurdy (1997)

The outlook wasn’t brilliant for the Brownie nine that day;

They were moving from St. Louis – to a place quite far away,

And all because Bill Veeck had said, “I can’t afford to stay,”

The team was playing their last game – in that fabled Brownie way.

With hopes of winning buried deep – beneath all known dismay,

The Brownies ate their cellar fate, but still charged out to play.

In aim to halt a last hard loss – in a season dead since May,

They sent Pillette out to the mound – to speak their final say.

The White Sox were that last dance foe – at the former Sportsman’s Park,

And our pitcher pulsed the pallor of those few fans in the dark.

To the dank and empty stands they came, – one final, futile time,

To witness their dear Brownies reach – ignominy sublime.

When Mickelson then knocked in Groth – for the first run of the game,

It was to be the last Browns score, – from here to kingdom came.

And all the hopes that fanned once more, – in that third inning spree,

Were briefly blowing in the wind, – but lost eternally.

For over seven innings then, – Dee bleached the White Sox out,

And the Browns were up by one to oh, – when Rivera launched his clout.

That homer tied the score at one, – and then the game ran on.

Until eleven innings played, – the franchise was not gone.

But Minnie’s double won the game – for the lefty, Billy Pierce,

And Dee picked up the last Browns loss; – one hundred times is fierce!

And when Jim Dyck flew out to end – the Browns’ last time at bat,

The SL Browns were here no more, and that was that, – was that!

Oh, somewhere in this favored land, the sun is shining bright;

The band is playing somewhere, and somewhere hearts are light;

And somewhere men are laughing, – and little children shout,

But there’s no joy in Sislerville, – the Brownies have pulled out.

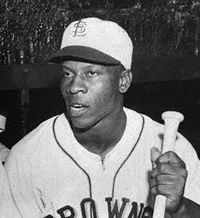

Willard Brown was one of those older, out-of-the-shadows players who glanced his way through organized baseball during the early days of its desegregation. He got there in time to leave one very indelible mark, but not early enough to use all of his abilities in their prime form, and not late enough to find any real place for himself in the major leagues among a more receptive crowd of accepting white teammates. No indeed. An older Willard Brown got there playing for a team that still overflowed in 1947 with some old school white racists.

Willard Brown was one of those older, out-of-the-shadows players who glanced his way through organized baseball during the early days of its desegregation. He got there in time to leave one very indelible mark, but not early enough to use all of his abilities in their prime form, and not late enough to find any real place for himself in the major leagues among a more receptive crowd of accepting white teammates. No indeed. An older Willard Brown got there playing for a team that still overflowed in 1947 with some old school white racists. hitting .179 in 21 games with the Browns, Willard Brown left the big leagues and returned to the familiar confines of his more comfortable life among the Monarchs in Kansas City. That winter of 47-48, Brown went to Puerto Rico and batted .432 with 27 homers and 86 RBI in only 60 games, earning for himself yet another nickname as Ese Hombre or – “That Man”.

hitting .179 in 21 games with the Browns, Willard Brown left the big leagues and returned to the familiar confines of his more comfortable life among the Monarchs in Kansas City. That winter of 47-48, Brown went to Puerto Rico and batted .432 with 27 homers and 86 RBI in only 60 games, earning for himself yet another nickname as Ese Hombre or – “That Man”. That’s Houston Buffs President Allen Russell in the business suit and hat at the far left of today’s featured first photo. He’s showing some kind of report in early 1950 to St. Louis Cardinal coaches Runt Marr (next to Russell) and Freddy Hawn (far right). That’s Kemp Wicker, the first of two managers who commanded the Good Ship Buffalo at the start of the ’50 season wearing the “Houston” jersey. Little Benny Borgmann would soon replace Wicker and manage the Buffs for most of their ride into the Texas League cellar that most inglorious year, but that kind of field performance disaster never stopped Allen Russell. It simply provided a different kind of marketing challenge.

That’s Houston Buffs President Allen Russell in the business suit and hat at the far left of today’s featured first photo. He’s showing some kind of report in early 1950 to St. Louis Cardinal coaches Runt Marr (next to Russell) and Freddy Hawn (far right). That’s Kemp Wicker, the first of two managers who commanded the Good Ship Buffalo at the start of the ’50 season wearing the “Houston” jersey. Little Benny Borgmann would soon replace Wicker and manage the Buffs for most of their ride into the Texas League cellar that most inglorious year, but that kind of field performance disaster never stopped Allen Russell. It simply provided a different kind of marketing challenge. As modeled in the photo by the Buffs’ sluggung first baseman Jerry Witte, the Buffs agreed to wear shorts, as I also covered in a recent article. The ostensible reason given for this change was that the Buffs wanted to do all they could to make sure their players were made as comfortable as possible in the searing, humid Houston summer heat.

As modeled in the photo by the Buffs’ sluggung first baseman Jerry Witte, the Buffs agreed to wear shorts, as I also covered in a recent article. The ostensible reason given for this change was that the Buffs wanted to do all they could to make sure their players were made as comfortable as possible in the searing, humid Houston summer heat. In 1946, the year that Russell took over as Buffs President, the Buffs drew 161,000 fans and the major league St. Louis Browns drew 526,000. The very next year, 1947, the Buffs outdrew the Browns by 326,000 to 282,000. By 1948, the Buffs again won the gate battle, 401,000 to 336,000. The Browns edged a bad Buffs team in 1949 by 271,000 to 254,000, but an 8th places Buffs club in 1950 still edged a 7th place Browns club by 256.000 to 247,000. The Buffs won again in 1951 by 333,000 ro 294,000 By 1952, St. Louis was reaping the benefits of Bill Veeck’s second year at the Browns helm. The Browns outdrew the Buffs by 519,000 to 195,000 in 1952 – and they edged them again in 1953, the last year of the Browns, by a 297,000 to 204,000 count.

In 1946, the year that Russell took over as Buffs President, the Buffs drew 161,000 fans and the major league St. Louis Browns drew 526,000. The very next year, 1947, the Buffs outdrew the Browns by 326,000 to 282,000. By 1948, the Buffs again won the gate battle, 401,000 to 336,000. The Browns edged a bad Buffs team in 1949 by 271,000 to 254,000, but an 8th places Buffs club in 1950 still edged a 7th place Browns club by 256.000 to 247,000. The Buffs won again in 1951 by 333,000 ro 294,000 By 1952, St. Louis was reaping the benefits of Bill Veeck’s second year at the Browns helm. The Browns outdrew the Buffs by 519,000 to 195,000 in 1952 – and they edged them again in 1953, the last year of the Browns, by a 297,000 to 204,000 count.