Buddy Bolden died in a Louisiana hospital for the criminally insane in 1931 at the age of 54, but by that time, the legendary first cornet in jazz history was probably still being charged with petty street crimes in New Orleans that he never committed. Back then, the New Orleans police didn’t need 100% accuracy in their identification of black criminals to find a man guilty. If a guy was black, had a name that was similar to a known criminal, and if he remotely resembled the known miscreant, the police were likely to pass on his offense to the record of the established identity.

In addition to his musical genius and wide awake performances at the Funk Butt Hall on Rampart Street in New Orleans, Buddy Bolden had been guilty of some mental illness and alcohol addiction issues in his earlier life that had transformed him into a New Orleans street character, a man well-known enough into becoming the likely suspect in cases of public intoxication, domestic violence, or simple assault between drinking-buddy strangers.

A friend of mine, Donald M. Marquis of Goshen Indiana, moved to New Orleans in 1962 and spent the next sixteen years of his life in search of the real Buddy Bolden, the first great horn man of jazz. What he ran into for the longest while were dead ends – dead ends helped along by the posting of erroneous public information and the absence of primary source artifacts and people who actually knew Bolden. It didn’t get any easier with time. After all, Marquis began his research some 31 known years after the death of his subject. About all that still floated around in 1962 in easy-to-find plain sight were the bad police records and the secondary source testimony of children and grandchildren who had heard their elders talk of the man and his magnificent horn-playing down at the Funky Butt Hall. Those things – and a couple of grainy old photos, one of Buddy with his band and another solo shot of him holding his cornet – were all that remained available to the near-naked eye.

Then, one day deep in years later, Don Marquis found his way to a descendant of Buddy Bolden who had been holding to her own a treasure trove of accurate primary source data – data that included the first really good image of the man and further documentation of what actually had happened to him.

For those of you who may be interested, Don published his seminal findings in 1978 as “The Search for Buddy Bolden: First Man of Jazz” by Donald M. Marquis. A revised paperback version of the book is now available at Amazon.com. There is also an independent film, or made-for-TV movie based largely on Marquis’ findings, coming out sometime later this year. I don’t know the title.

For our purposes, the experience of researcher-writer Donald M. Marquis serve to highlight some of the more serious issues facing the lone independent scholar. Unless you possess the time and ability to live as modestly as Marquis did for years and years, it is likely that your hard-to-wrap subject shall always elude you.

On the other hand, with the camaraderie of a small army of like-minded and dedicated people working with you, much is possible. Put that realization together with a clear understanding of primary and secondary sources – and we move far closer to getting the link established between connected facts in history,

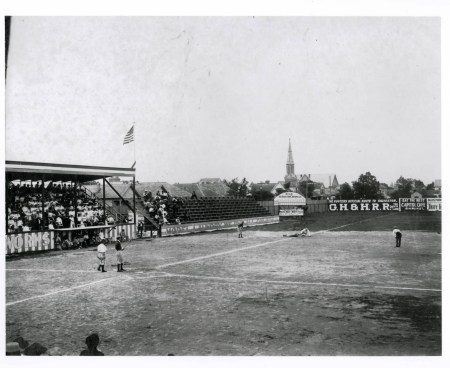

This is the understanding and small wisdom that our SABR team takes with us into our impending study of “Houston Baseball, 1861-1961: The First One Hundred Years.” We are on our way together to the establishment of a much clearer factual picture on the history of baseball in our little area of the world.

To get a handle on primary and secondary source material distinctions, the following summary of same from Wikipedia spells them out about as well as they may be expressed. I will leave you with their words as our notes on the day:

Primary source is a term used in a number of disciplines to describe source material that is closest to the person, information, period, or idea being studied.

In the study of history as an academic discipline, a primary source (also called original source or evidence) is an artifact, a document, a recording, or other source of information that was created at the time under study. It serves as an original source of information about the topic. Similar definitions are used in library science, and other areas of scholarship. In journalism, a primary source can be a person with direct knowledge of a situation, or a document created by such a person.

Primary sources are distinguished from secondary sources, which cite, comment on, or build upon primary sources, though the distinction is not a sharp one. A secondary source may also be a primary source and may depend on how it is used. “Primary” and “secondary” are relative terms, with sources judged primary or secondary according to specific historical contexts and what is being studied.