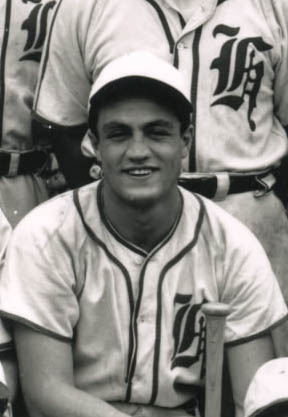

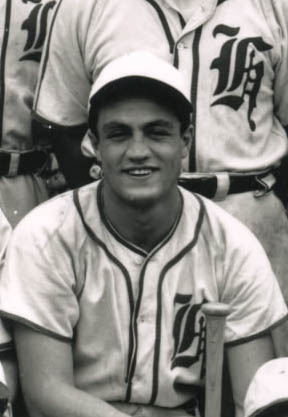

Jim Basso, Houston Buffs, 1946-48.

Jim Basso lived as the personification of the career minor leaguer back in the pre and post World II years. He loved baseball, he played the outfield well, he hit with some punch, he didn’t really have much education or a lot of skills that gave him a good or passionate alternative to the game, and he always dreamed of breaking into the big leagues with some team, somewhere along the way by just hanging in there long enough, showing up every spring, whether he was hurt or not, and giving it his best, no matter where he was playing.

The big leagues never happened for Jim Basso. Sadly, he went to his grave, forever regretting the fact that he never got so much as a single time at bat with any big league club in a regular season game.

“It would’ve meant a lot to me,” Jim once told me. “Just to know that I had gotten into into the big record book as one of the few players who made it to the big leagues would’ve meant everything to me.”

It wasn’t meant to be, but it surely wasn’t because Jim Basso didn’t have the tools or performance record to at leat earn a trial in the bigs. He simply played in the era of great major league club exclusivity. With only sixteen total big league clubs in both major leagues until expansion started in 1961, Jim Basso belongs to a large, not-so-exclusive legion of lost opportunity. A lot of ball players who would at least get a playing look today never even got there back then. With the reserve clause governing all player movements prior to free agency, a lot of players also missed the majors because the parent club either couldn’t find roster room or didn’t want certain players from falling into the hands of their big league rivals. We will never know for sure how many players actually had their MLB careers denied by a parent club that may have been hoarding talent in the minors in self-defense.

James Sebastian (Jim) Basso (BR/TR, 6’0″, 185 Lbs.) was born in Omaha, Nebraska on October 5, 1919. Signing with the St. Louis Cardinals, but eventually winding his way into the systems of the Reds, Braves, and White Sox, Basso compiled a 13-season minor league record (1941, 1946-57) and a three-season stint as a member of the Houston Buffs (1946-48). Jimmy didn’t even get into a game from the roster of the ’48 Buffs before he was dealt away, but he stayed long enough to make the Houston area and his place in Pearland a permanent residence beyond baseball.

Jim Basso was a pretty fair country hitter. His career batting average was .297 with a slugging average of .464. He racked up 1,815 total hits that included 335 doubles, 57 triples, and 191 home runs. Wow! Do you think a guy with Basso’s stats might have gotten an AB or two in the big leagues somewhere in 2010?

For better, but mostly worse, Jim Basso played hurt.

“You had to play hurt back then,” Jim often said. “If you took a day off to nurse an injury back in my day, you knew that you just might wake up the next morning to find somebody else wearing your jock strap. You couldn’t let that happen. You had to play, even if it made things worse on your injury.”

Jim Basso also played a few winters in Cuba during his career. He even managed to meet Ernest Hemingway when the great American writer invited Basso and some of his teammates over to the house for drinks in the evening.

One day, late in Jim’s life, I drove out to Pearland with former Buff Jerry Witte to visit. During our stay, Jim said he wanted to show me his workshop in the garage so we walked out in the back to see the place in the detached building that held it all. It was quite nice, but the summer heat had turned the place into a boiler room.

It was then that I looked over to a work shelf and spied a single book in place. Since it was a book, I had to walk over and see what it was.

It turned out to be a first edition copy of “The Old Man and the Sea” and it had been personally autographed “To my good friends, Jim and Connie Basso! Affectionately, Ernest Hemingway.”

Ernest Hemingway & Jim Basso in Cuba, 1952, (center); unidentified ballplayers on flanks.

“Jim,” I cried out a little too school marmishly. “You’ve got to get this book inside and out of this light and heat right away!”

“Yeah?” Jim asked.

Yeah!” I affirmed.

Once I explained the problem, Jim jumped on it himself. He picked up the book and took it inside. Then he told me the story of how he and his wife Connie had met Hemingway in Cuba, and how he and his fellow ball players had enjoyed drinking and talking baseball with the great author in the Cuban evenings at Hemingway’s home.

Jim Basso passed away on May 21, 1999 in Pearland, Texas at the age of 79. He took with him so many good stories, a heart of gold, an unending passion for the game of baseball, and that awful nobody-could-take-it-from-him regret that he never got that time at bat in the majors.

Since the Hemingway book discovery, I’ve thought of Jim Basso as the living baseball symbol of the old fisherman in Hemingway’s book. For many years, Jim Basso went down to the Sea of Baseball every morning, always hoping to catch the big fish of big league opportunity. He never even hooked his dream monster, but he never gave up. It was not within his heart to do so. He kept going back to the sea each day for as long as he could. And then he went home each night to sleep. And to dream again of the lions. And to wake up later and read the box scores in the newspapers. And to learn the latest stories of the great DiMaggio.

Goodnight, Jim Basso, wherever you may now be. To those of us who knew and loved you, you will always be one of our major leaguers. No matter what.