L>R: MONTE IRVIN, LARRY DIERKER, JIMMY WYNN.

The Larry Dierker Chapter of SABR (The Society for American Baseball Research) had a tag-em-all meeting yesterday, Saturday, January 29th, from 2-4 PM in celebration of our National SABR Day gathering at the Houston Sports Museum inside the Finger Furniture Store located on the historic site of old Buff Stadium (1928-1961) on the north side of the Gulf Freeway at Cullen. Sixty-eight members and guest signed the reception book and another twenty to thirty later unregistered show-ups ran the attendance count close to 100. Those who stayed for the whole baseball rodeo hardly missed a subject that had anything to do with the game, and especially with Houston history of same.

Chapter Leader Bob Dorrill

Chapter leader Bob Dorrill spoke about the importance of National SABR Day as the one day of the year that all chapters unite through out the land in a united effort to promote the purposes of SABR to all persons interested in the preservation and celebration of baseball’s history.

As General Manager of our vintage base ball club, The Houston Babies, I received a beautifully framed team photo of the unforgettable club itself, thanks to a brief, but forever appreciated acknowledgment from field Manager Bob Dorrill. All I can say is thanks. I love you guys to pieces. – I just wish that you’d stop going to pieces in the middle of a game. Maybe this year will be better. Go further – I really think it will be. Take it one more foot slide forward: I believe in you, Babies! This year we are going to scorch the pastures of Southeast Texas with all the power of our innate, but, so far, unused playing ability.

In that light, Chapter namesake Larry Dierker talked about Houston’s early professional start in the 19th century as the Houston Babies. On a kidding note, Dierker wondered if any city or town ever began with a more humiliating nickname. Seriously, he then launched into an interesting summary of how Houston flowed and ebbed as a baseball town over the years. He painted a moving picture of the mind with his account of how Houston Buffs fans once started out from homes as far away as five miles away and began their walks to the ball games played at Buff Stadium, the park pictured in the mural behind the table in first featured photo. – By the time these walking fans reached the ball park, their singular steps had flowed together into a river of Buff fans, now converging upon that earlier version of our baseball heaven.

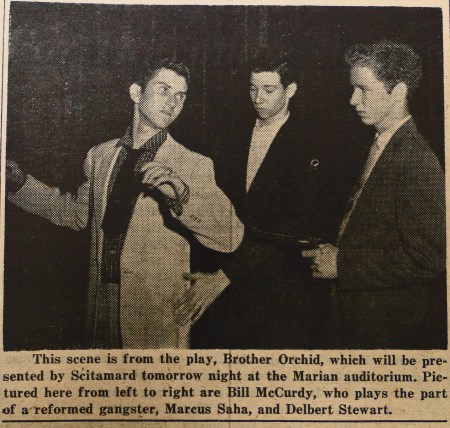

Jimmy Wynn and Monte Irvin both talked openly about their playing days in response to questions from the crowd. Scott Barzilla of SABR spoke briefly about his new book, “The Hall of Fame Index,” and visitor Dick “Lefty” O’Neal was also recognized for his book, “Dreaming of the Majors; Living in the Bush.” Those two gentlemen, along with Jimmy Wynn and SABR’s Bill McCurdy, who recently collaborated on “Toy Cannon: The Autobiography of Baseball’s Jimmy Wynn,” were also on hand after the meeting to sign copies of their various works.

Former Houston Buff Larry Miggins told some of his best anecdotal baseball stories. No one tell ’em quite as well as the old Irishman. Miggins and Vin Scully attended the same high school in New York City. While they were there, Scully predicted that he would be broadcasting major league games and would be behind the mike on the date that Miggins broke into the big leagues with a home run – and that’s exactly what happened. Scully was calling the game for the Brooklyn Dodgers when Larry Miggins broke into the big leagues for the St. Lois cardinals by hitting a home run off Preacher Roe. – How’s that one for A SABR Day spine-chiller?

Ton Kleinworth of SABR designed and presented a brand new trivia contest called “Name That Player.” SABR’s Mack WIlson then followed Tom with a nice little multiple choice trivia contest. The winner, Mark Wernick of SABR, received a Larry Dierker action figure donated by Mike Acosta of the Houston Astros.

Dave Raymond of SABR and the Houston Astros radio broadcasting crew gave us a nice conservative, but optimistic evaluation of the 2011 club. Dave sees the Astros as having a lot more pop up the middle with the additions of Cliff Barnes at shortstop and Bill Hall at second base. Both are hardscrabble infielders with long ball capacity, but low OBP figures. Low OBP was a problem last year and needs to improve, according to both Raymond anyone else who is paying attention. The pitching is adequate and we may be only a key player development breakthrouh away from getting back into the thick of things.

Greg Lucas of SABR and Fox Sports followed Raymond with a nice cap on the NL Central for 2011. According to Greg, the Cards, Brewers, and Reds are the frontrunners, but the Astros and Cubs may get back into contention on an eye-flick. Lucas only discounts the Pirates due to their bad pitching.

Between the lines of these comments from Raymond and Lucas, the gentle hum of spring hope was beginning to germinate – and isn’t that exactly what it’s supposed to do this time of year?

As for me, I dove deep into history. I (Bill McCurdy) offered the challenge that we need to develop a chapter plan for researching and accurately writing Houston early baseball history from 1861 to 1961. That century span covers the documentable era of time that passed between the formation of the first Houston Base Ball Club through the last season of our minor league Houston Buffs.

Curator Tom Kennedy welcomed one and all to the beautifully refurbished Houston Museum of Sports History. Couched on the site of the still embedded home plate from Buff Stadium on its original spot, owner Rodney Finger and the Finger family deserve incredible appreciation for all they have done and continue to do to preserve this important artifact marking on the trail of Houston’s baseball history. Now, if we can only rouse the same effort on the task of tagging and noting the significance of earlier venues, where the first Houston Base Ball Club was formed in a room above J.H. Evans’s store on Market Square in 1861; where the Houston Base Ball Park existed downtown when our first professional club took the field here in 1888; and when and where, for sure, the first game was played at West End Park on Andrews Street. I refuse to go in the ground until those facts are sorted out and published somewhere by someone who cares about Houston baseball history.

The Giants finally retired Monte Irvin's #20 in 2010.

My extra treat was all tied into the ninety minutes or so that I spent driving Hall of Famer Monte Irvin to and from the meeting, between downtown and the west side. I couldn’t begin to share everything we talked about in the space we have here – and I wouldn’t, anyway, on the grounds that he spoke to me in confidence on a lot of baseball subjects with opinions that are his and his alone to divulge in a public forum.

You probably have figured this one out from hearing him speak: Monte Irvin is one of the kindest, truest gentleman you could ever hope to meet. He attributes his long life to having a wonderful, guiding mother and a whole lot of luck. When pressed, he will concede that genes help out too, but he clings pretty close to the wisdom too that “to become an older person you first have to survive being a younger person” and, as far as Monte is concerned, that’s where the luck comes in.

I can share one Monte Irvin Story. Almost apologetically, I asked Monte about that 1951 steal of home in the first inning of Game One in the Giants’ 5-1 World Series victory over the Yankees. I realize that I probably was about the 5,000th fan to ask, but I couldn’t help myself.

Monte was on third with a triple. Allie Reynolds and Yogi Berra were the battery for the Yankees. And Bobby Thomson, a right-handed batter, as you well better know by now, was at the plate. All of a sudden, Monte breaks for the plate. He is stealing home, and he does so successfully, sliding under Berra’s tag for the Giants’ second run in the first stanza on one of the too few days the ’51 Series went the Giants’ way,

“When did you know for sure you were going to try that steal of home?” I asked.

“I pretty much knew it going in,” Monte says. “I had stolen home five or six times during the season and I also was quite familiar with that slow deliberate delivery style of Allie Reynolds. Reynolds threw hard to make up for the slow delivery, but he usually threw high, which was what he was doing in that moment with our batter, Bobby Thomson. I knew I had a good chance of making it. I also had talked with Leo Durocher prior to the game and he had given me the green light to try, if I saw the opportunity. By the time Reynolds saw what I was doing, he was already in motion to launch another high, hard one. That didn’t change. The pitch came in high and hard. I came in low and hard. By the time Yogi can get his glove down to tag me, I’m safe. Had Allie thrown it low and hard, he probably would had me. It didn’t work out that way.”

Near 90 showed up for SABR Day in Houston

Before we arrived back at Monte’s place at the end of the day, he had started reminiscing about the many Giant teammates that are now gone. That pretty much is going to happen when you live as long as Monte has. He turns 92 on February 25th.

I finally blurted out, “Listen, Monte, you may have gotten this far by being lucky, but you are here for a reason. And part of that reason, as I see it, is to help baseball people remember what’s really important about the game and life itself. We need you to hang around forever as our role model, our teacher, and our national treasure.”

Monte smiled. “I’ll give it my best shot,” he promised.

SABR Day in Houston was a great day in general. A lucky day for some of us. And a blessed day for us all.