We just returned last night from a two-day train trip to Lake Charles, but that’s a story for another day. This morning I want to tell you about another ex-Cardinal and former Buff pitcher who also just happened to be a good friend. His name was George “Red” Munger, a name that won’t be lost to the memories of anyone who was around during all those 1940s years of great Cardinal teams. Red Munger just happened to be a big part of that success. The native Houstonian and lifelong East Ender was smack dab in the middle of that zenith era in Cardinal history, even though he lost all of 1945 and most of the championship 1946 season to military service. Red still managed to return in time to make his own contributions to the Cardinals’ victory over the Boston Red Sox in the 1946 World Series.

We just returned last night from a two-day train trip to Lake Charles, but that’s a story for another day. This morning I want to tell you about another ex-Cardinal and former Buff pitcher who also just happened to be a good friend. His name was George “Red” Munger, a name that won’t be lost to the memories of anyone who was around during all those 1940s years of great Cardinal teams. Red Munger just happened to be a big part of that success. The native Houstonian and lifelong East Ender was smack dab in the middle of that zenith era in Cardinal history, even though he lost all of 1945 and most of the championship 1946 season to military service. Red still managed to return in time to make his own contributions to the Cardinals’ victory over the Boston Red Sox in the 1946 World Series.

George David “Red” Munger was born in Houston on October 4, 1918. Like most able bodied, athletically inclined East Enders of his era, Red was drawn to sandlot and Houston youth organized baseball at an early age. I never asked Red if he made it to the opening of Buff Stadium on April 11, 1928, but I wouldn’t be surprised if he did find a way to get in as a nine-year old baseball fanatic. He lived in the neighborhood and he was an avid Buffs fan long prior to his two short stints with the 1937 and 1938 Houston club. Red also made it downtown as a young kid to old West End Park prior to the opening of Buff Stadium. The little I know today from years past about West End Park still comes mainly from what I was told by Red Munger and former Browns/Senators catcher Frank Mancuso. My regret is that I didn’t make a focused attempt in earlier years to drain their brains of all they each knew about the facts and lore of West End Park. Recording history gets a lot tougher once all the eye witnesses and other primary sources are gone.

Red Munger was signed by Fred Ankenman of the Houston Buffs as a BR/TR pitcher following his 1937 graduation from high school. The Buffs sent Red to New Iberia of the Evangeline League where he promptly racked up a 19-11 record with a 3.42 ERA in his first season of professional ball. Red finished the ’37 season with Houston, posting no record and a 2.45 ERA in limited work. 1938 found Red back at New Iberia, where his 10-6 record quickly earned him a second promotion to the higher level Buffs club. Munger only posted a 2-5 mark for the ’38 Buffs, but his improvement over the next four seasons at Asheville (16-13), Sacramento (9-14) (17-16) and Columbus, Oho (16-13) finally earned him a shot the withthe big club. Red went 9-5 with a 3.95 ERA at St. Louis in 1943; he then went 11-3, with an incredible 1.34 ERA with the 1944 Cardinals.

Red Munger’s 1944 success earned him a place on the National League All Star team, but before he got to play, he was called up and inducted into the army for military service. Red achieved some great, but unsurprising success in service baseball. He was just too good for the competition he faced at that rank amateur level. Once Red obtained his second lieutenant’s commission and was assigned to developing the baseball program at his base in Germany, he just stopped playing in favor of full time teaching. He even said that he had no heart for pitching or hitting against competitors who were too young, too green, and too unable to compete against him.

achieved some great, but unsurprising success in service baseball. He was just too good for the competition he faced at that rank amateur level. Once Red obtained his second lieutenant’s commission and was assigned to developing the baseball program at his base in Germany, he just stopped playing in favor of full time teaching. He even said that he had no heart for pitching or hitting against competitors who were too young, too green, and too unable to compete against him.

Red returned from the service in late 1946, just in time to pitch a few innings in the late season and to throw a complete game win over Boston at Fenway Park in Game Four of the World Series. The 12-3 Cardinal victoy tied the Series at 2-2 in games as Munger also benefitted from a twenty hit Cardinal attack on Red Sox pitching. Over the next five seasons with the Cardinals, Red posted two outstanding years in 1947 (16-5, 3.37) and 1949 (15-8, 3.88). His other years were fairly mediocre. The nadir in Red Munger’s career came falling down upon him in 1952. He was dealt to the Pittsburgh Piartes and his combined record with St. Louis and Pittsburgh was 0-4 with a 7.92 balloon-level ERA for the year.

Red would have one more year in the majors in 1956 when, after returning from Hollywood of the Pacific Coast League after four seasons, he went 3-4 with a 4.04 ERA for the Pirates. Munger had earned his way back with a 23-8, 1.85 ERA mark at Hollywood in 1955. After two more piddling years in the minors, Red Munger retired after the 1958 season and closed the door on a twenty year playing career. He left beind a respectable major league mark of 77-56 with an ERA of 3.83. All told, Red Munger pitched for twenty seasons from 1937 to 1958.

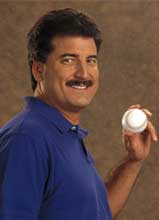

After baseball, Red Munger worked as a minor league pitching coach and also as a private investigator for the Pinkerton agency. He later developed diabetes and passed away from us on July 23, 1996 at age 77. I took that last picture of him in the 1946 Cardinals replica cap on a visit to his home, about two weeks before he died. Red gave me that cap that he wore in the picture at left on the same day. I have treasured it ever since.

After baseball, Red Munger worked as a minor league pitching coach and also as a private investigator for the Pinkerton agency. He later developed diabetes and passed away from us on July 23, 1996 at age 77. I took that last picture of him in the 1946 Cardinals replica cap on a visit to his home, about two weeks before he died. Red gave me that cap that he wore in the picture at left on the same day. I have treasured it ever since.

Red was generous to a fault. I never accepted any of his offered gifts of authentic artifacts, but strangers to the man were not as kind. I advised Red to save his things for family and history, but Red had a mind and heart all his own. One time a guy came to interview Red a single time. In the process, Red warmed up to the guy and offered the man his 1938 Buffs uniform, which he somehow managed to have kept for all those years. The man took it and was never seen again. I think that stung Red pretty deeply.

Red loved talking about the everyday action of life in the big leagues. His stories go way beyond the scope of a single blog article. One of his early “edge” lessons came from Warren Spahn. “We were up in Boston, playing the Braves,” Red drolled, “and old Spahn was pitching against me. He was doing so well that I decided to pay closer attention to his mechanics. It didn’t take me long to find the source of his ‘edge’ because I was looking for it when no else, even the umpires, apparently weren’t. What Spahnie was doing was gradually covering the pitching rubber with that black dirt they used to have on their mound at Braves Field. Once that was done, he would simply start his windup about one foot closer to the plate. With good control, a pitcher becomes much more effective at 59 feet six inches than he is at sixty feet six inches. I know. I tried it after watching Spahn do it. For me, it was good enough to produce a win. No, I never talked about it with Spahn, but I feel sure he knew what I was doing too. We both had a reason to keep our mouths shut, now didn’t we?”

Red Munger enjoyed watching position players with strong arms and then imagining how effective they might be as pitchers. His favorite subject that last summer of 1996 was Ken Caminiti – and this was long before all the disclosures about Ken’s mind-altering and performace-enhancing drug abuse. Red Munger just liked the man as a gifted athlete. Caminiti fit the bill on what Red Munger was looking for in pitching potential. “Give me a guy with a strong arm and I can probably teach him the other things he needs to know about pitching. I can’t teach a guy how to have a strong arm – and as far as I can see, no one else can do that either beyond telling him to work out and hope for the best. As far as I’m concerned in the matter of good arms, you’ve either got one or you don’t.”

Red Munger enjoyed watching position players with strong arms and then imagining how effective they might be as pitchers. His favorite subject that last summer of 1996 was Ken Caminiti – and this was long before all the disclosures about Ken’s mind-altering and performace-enhancing drug abuse. Red Munger just liked the man as a gifted athlete. Caminiti fit the bill on what Red Munger was looking for in pitching potential. “Give me a guy with a strong arm and I can probably teach him the other things he needs to know about pitching. I can’t teach a guy how to have a strong arm – and as far as I can see, no one else can do that either beyond telling him to work out and hope for the best. As far as I’m concerned in the matter of good arms, you’ve either got one or you don’t.”

Red Munger didn’t live long enough to see the steroid era coming, but I think I can tell you this much: He would not have liked it at all. Red Munger may have taken the “Spahn Edge” on that mound dirt in Boston, but he honestly believed that baseball was a game to be played with the natural abilities that came to a player at birth. I asked him about the use of alcohol and stimulants like amphetamines once. “A lot of people drank back in my time, but beer or booze never made anybody a better pitcher. As for the use of drugs, we didn’t have that kind of stuff going on in my day. We just got out there and played the game with what the God Lord gave us through Mother Nature. If that wasn’t good enough, a player had to start looking for another line of work.”

Recreationally, Red used to say that he enjoyed Crosley Field as one of his favorite ballparks. “My liking of the place had nothing to do with me pitching better there.” Red stressed. “I just liked watching old Hank Sauer of the Reds running up that hill in left field, trying to catch a fly ball without falling down.”

Red Munger would have loved Minute Maid Park!

Ken Boyer was neither the first nor the last of the baseball playing Boyer boys. He was simply the best of the six brothers who ventured into the arena of the professional over the two decades that followed World War II. The Alba, Missouri native was also just one among the pack of the fourteen kids born to the rural Boyer family who discovered baseball as a way up and out to the larger world when he began his career with Class D Lebanon in 1949. Ken started as a pitcher, going 5-1 with a 3.42 ERA in ’49, but he also did something else that first year that distracted the parent Cardinal organization from seeing his future on the mound. He hit .455 for the season. Once Boyer’s pitching record slipped to 6-8 with a 4.39 ERA in 1950 with Class D Hamilton, while his battting average stayed up there at .342, the Cardinals felt that they had to keep the guy in the lineup as a position player. Ken made the transition just fine as a third baseman for Class A Omaha in 1951. He batted .306 with 14 HR and 90 RBI before going into the service for two two years (1952-53) during the Korean War. Ken Boyer resumed his career in 1954 as a third baseman for the Houston Buffs. His career took off like a rocket. Batting .319 with 21 homers and 116 runs batted in for the ’54 Buffs, Boyer led the club to the Texas League championship – as he also launched his own career to the major league level in 1955.

Ken Boyer was neither the first nor the last of the baseball playing Boyer boys. He was simply the best of the six brothers who ventured into the arena of the professional over the two decades that followed World War II. The Alba, Missouri native was also just one among the pack of the fourteen kids born to the rural Boyer family who discovered baseball as a way up and out to the larger world when he began his career with Class D Lebanon in 1949. Ken started as a pitcher, going 5-1 with a 3.42 ERA in ’49, but he also did something else that first year that distracted the parent Cardinal organization from seeing his future on the mound. He hit .455 for the season. Once Boyer’s pitching record slipped to 6-8 with a 4.39 ERA in 1950 with Class D Hamilton, while his battting average stayed up there at .342, the Cardinals felt that they had to keep the guy in the lineup as a position player. Ken made the transition just fine as a third baseman for Class A Omaha in 1951. He batted .306 with 14 HR and 90 RBI before going into the service for two two years (1952-53) during the Korean War. Ken Boyer resumed his career in 1954 as a third baseman for the Houston Buffs. His career took off like a rocket. Batting .319 with 21 homers and 116 runs batted in for the ’54 Buffs, Boyer led the club to the Texas League championship – as he also launched his own career to the major league level in 1955. John Hernandez was the star lefthanded battting and throwing first baseman of the 1947 Texas League and Dixie Series Champion Houston Buffs. After an early acquisition from Oklahoma City in 1947, Hernandez did very well in Houston. His .301 batting average, 17 home runs, and 78 runs batted in were a big part of the reason the Buffs enjoyed one of their finest seasons of all time that year, and that doesn’t even take into account his defensive contributions with the glove. The guy was a sweet fielding wizard at his position.

John Hernandez was the star lefthanded battting and throwing first baseman of the 1947 Texas League and Dixie Series Champion Houston Buffs. After an early acquisition from Oklahoma City in 1947, Hernandez did very well in Houston. His .301 batting average, 17 home runs, and 78 runs batted in were a big part of the reason the Buffs enjoyed one of their finest seasons of all time that year, and that doesn’t even take into account his defensive contributions with the glove. The guy was a sweet fielding wizard at his position. John Hernandez’s son Keith grew up to be one of the greatest defensive first baseman in major league history. Keith Hernandez’s 11 straight gold glove awards is a mjor league record. He also wan’t too shabby as a hitter either, leading the National League in hitting in 1979 with a .344 average at St. Louis. Keith Hernandez also was a leading force on two World Series ball clubs, the 1982 St. Louis Cardinals and the 1986 New York Mets. What a lot of people don’t know is that Keith Hernandez always used his dad as his anchor man coach for helping him straighten out anything that was getting in the way of his best game, and that assistance covers a lot of ground in this instance.

John Hernandez’s son Keith grew up to be one of the greatest defensive first baseman in major league history. Keith Hernandez’s 11 straight gold glove awards is a mjor league record. He also wan’t too shabby as a hitter either, leading the National League in hitting in 1979 with a .344 average at St. Louis. Keith Hernandez also was a leading force on two World Series ball clubs, the 1982 St. Louis Cardinals and the 1986 New York Mets. What a lot of people don’t know is that Keith Hernandez always used his dad as his anchor man coach for helping him straighten out anything that was getting in the way of his best game, and that assistance covers a lot of ground in this instance.

We just returned last night from a two-day train trip to Lake Charles, but that’s a story for another day. This morning I want to tell you about another ex-Cardinal and former Buff pitcher who also just happened to be a good friend. His name was George “Red” Munger, a name that won’t be lost to the memories of anyone who was around during all those 1940s years of great Cardinal teams. Red Munger just happened to be a big part of that success. The native Houstonian and lifelong East Ender was smack dab in the middle of that zenith era in Cardinal history, even though he lost all of 1945 and most of the championship 1946 season to military service. Red still managed to return in time to make his own contributions to the Cardinals’ victory over the Boston Red Sox in the 1946 World Series.

We just returned last night from a two-day train trip to Lake Charles, but that’s a story for another day. This morning I want to tell you about another ex-Cardinal and former Buff pitcher who also just happened to be a good friend. His name was George “Red” Munger, a name that won’t be lost to the memories of anyone who was around during all those 1940s years of great Cardinal teams. Red Munger just happened to be a big part of that success. The native Houstonian and lifelong East Ender was smack dab in the middle of that zenith era in Cardinal history, even though he lost all of 1945 and most of the championship 1946 season to military service. Red still managed to return in time to make his own contributions to the Cardinals’ victory over the Boston Red Sox in the 1946 World Series. achieved some great, but unsurprising success in service baseball. He was just too good for the competition he faced at that rank amateur level. Once Red obtained his second lieutenant’s commission and was assigned to developing the baseball program at his base in Germany, he just stopped playing in favor of full time teaching. He even said that he had no heart for pitching or hitting against competitors who were too young, too green, and too unable to compete against him.

achieved some great, but unsurprising success in service baseball. He was just too good for the competition he faced at that rank amateur level. Once Red obtained his second lieutenant’s commission and was assigned to developing the baseball program at his base in Germany, he just stopped playing in favor of full time teaching. He even said that he had no heart for pitching or hitting against competitors who were too young, too green, and too unable to compete against him. After baseball, Red Munger worked as a minor league pitching coach and also as a private investigator for the Pinkerton agency. He later developed diabetes and passed away from us on July 23, 1996 at age 77. I took that last picture of him in the 1946 Cardinals replica cap on a visit to his home, about two weeks before he died. Red gave me that cap that he wore in the picture at left on the same day. I have treasured it ever since.

After baseball, Red Munger worked as a minor league pitching coach and also as a private investigator for the Pinkerton agency. He later developed diabetes and passed away from us on July 23, 1996 at age 77. I took that last picture of him in the 1946 Cardinals replica cap on a visit to his home, about two weeks before he died. Red gave me that cap that he wore in the picture at left on the same day. I have treasured it ever since. Red Munger enjoyed watching position players with strong arms and then imagining how effective they might be as pitchers. His favorite subject that last summer of 1996 was Ken Caminiti – and this was long before all the disclosures about Ken’s mind-altering and performace-enhancing drug abuse. Red Munger just liked the man as a gifted athlete. Caminiti fit the bill on what Red Munger was looking for in pitching potential. “Give me a guy with a strong arm and I can probably teach him the other things he needs to know about pitching. I can’t teach a guy how to have a strong arm – and as far as I can see, no one else can do that either beyond telling him to work out and hope for the best. As far as I’m concerned in the matter of good arms, you’ve either got one or you don’t.”

Red Munger enjoyed watching position players with strong arms and then imagining how effective they might be as pitchers. His favorite subject that last summer of 1996 was Ken Caminiti – and this was long before all the disclosures about Ken’s mind-altering and performace-enhancing drug abuse. Red Munger just liked the man as a gifted athlete. Caminiti fit the bill on what Red Munger was looking for in pitching potential. “Give me a guy with a strong arm and I can probably teach him the other things he needs to know about pitching. I can’t teach a guy how to have a strong arm – and as far as I can see, no one else can do that either beyond telling him to work out and hope for the best. As far as I’m concerned in the matter of good arms, you’ve either got one or you don’t.” From the late 1920s through the early 1950s, the St. Louis Cardinals operated a farm system that pretty much resembled the good and growing business of a fabled Hempstead, Texas watermelon grower. – Everything they harvested came out tasting sweet – with very little hassle from unwanted seeds.

From the late 1920s through the early 1950s, the St. Louis Cardinals operated a farm system that pretty much resembled the good and growing business of a fabled Hempstead, Texas watermelon grower. – Everything they harvested came out tasting sweet – with very little hassle from unwanted seeds. Back with Houston in 1941, the now 20-year old lefty showed that he had little left to prove in the minor leagues, even at his still tender age. In 1941, Pollet posted a 20-3 record for the Buffs and a league leading ERA of only 1.16. In all of Texas League history through 2008, only Walt Dickson’s 1.06 ERA, also posted with Houston back in 1916, beats the 1941 mark of Howie Pollet. Pollet also led the Texas League in strikeouts in 1941 with 151. The Buffs again won the Texas League straightaway race, this time by 16.5 games, but they lost in the first round of the playoffs for the Texas League pennant.

Back with Houston in 1941, the now 20-year old lefty showed that he had little left to prove in the minor leagues, even at his still tender age. In 1941, Pollet posted a 20-3 record for the Buffs and a league leading ERA of only 1.16. In all of Texas League history through 2008, only Walt Dickson’s 1.06 ERA, also posted with Houston back in 1916, beats the 1941 mark of Howie Pollet. Pollet also led the Texas League in strikeouts in 1941 with 151. The Buffs again won the Texas League straightaway race, this time by 16.5 games, but they lost in the first round of the playoffs for the Texas League pennant. After baseball, Howie Pollet returned to his adopted home of Houston and went into the insurance business with his former Buffs and Cardinals manager, Eddie Dyer. He even returned to baseball one year to serve as pitching coach for the Houston Astros. He was only age 53 when he died of cancer in 1974. Sometimes the good guys who arrive early also make an early exit. Baseball and Houston were the poorer from the early passing of the great Howie Pollet, but we’re glad we had him while we did.

After baseball, Howie Pollet returned to his adopted home of Houston and went into the insurance business with his former Buffs and Cardinals manager, Eddie Dyer. He even returned to baseball one year to serve as pitching coach for the Houston Astros. He was only age 53 when he died of cancer in 1974. Sometimes the good guys who arrive early also make an early exit. Baseball and Houston were the poorer from the early passing of the great Howie Pollet, but we’re glad we had him while we did.