AKA (TO ME) AS BOKE KNUCKLEMANN!

Dick Bokelmann was Boke Knucklemann! When I was a kid, I tried writing fictional action stories and I always used real people as models for my heroes and main characters. That’s how former Buffs pitcher Dick Bokelmann got to be “Boke Knucklemann.” It happened during the red hot Houston Buffs championship season of 1951. Even though I only wrote for my eyes only, I somehow picked up on the idea that a writer couldn’t use an actual name of a real person in his writings, but that changing the name enough to capture the model’s identity without using his actual name made it OK.

Like his real life namesake, Knucklemann pitched for the Buffs, but when he wasn’t pitching, he was fighting crime on the streets of Houston – knocking out bank robbers with knuckle balls that he carried with him in a bag as his weapon of choice. Well, they weren’t exactly knuckle balls while they were still in the bag, but that’s what they were destined to become – once the good guy “Bokeymann” got through throwing them.

Boke would run up on a robber coming out of a bank with his gun in one hand and his bag of loot in the other. Boke always stopped running toward his man once he got about 60′ 6″ away and then stare him down to a frightened halt. Then he would reach into his ball bag and pull out a weapon that he unleashed as a knuckler, one invariably heading straight for the robber’s face.

Long before Cassius Clay ever thought of it, these pitches of Boke Knucklemann carried with them the powers to both “dance like a butterfly and sting like a bee.” I always tried to convey these ideas in my 13-year old descriptions of all those “good rallies past evil” moments of final redemption. Although I burned or threw away all my original stories long ago, the big moment always went something like this:

“Gypsy Joe Stalinovich stalled in the doorway of the First National Bank on Main Street as he saw the athletic figure of Boke Knucklemann racing toward him. As Boke stopped some short distance away, Gypsy Joe also froze, with his gun in the left hand and his bag of loot in the right. Coming toward him hard was a bobbing, weaving baseball, which his eyes attempted to closely follow in flight. Suddenly, with his peepers now crossed in locked tracking mode on the incoming white meteor, there’s a loud SPLAT sound as Joe takes it right between the baby blues! – Cartoon butterflies encircle the evil Gypsy Joe’s injured cranium as he falls face flat forward to the pavement for one of the easiest robbery arrests in HPD history. Gypsy Joe’s message is one he’d like to pass on to all other mean and evil Houston crooks: ‘The Bokeymann will get you if you don’t watch out!'”

So, folks, I got a lot out of watching Houston Buffs baseball back in the day, and, thankfully, I was realistic enough back then to spare the public my adolescent storytelling efforts. The point of sharing that literary history with you now is simply to make this point: Those guys weren’t merely my baseball heroes. They also were my inspiration for heroic central casting and my writing character models.

The real Dick Bokelmann was a good enough pitcher in reality to actually need no additional superhero alter ego. As a knuckle balling reliever for the 1951 Houston Buffs in 27 of the 30 games he worked, Bokie won 10 and lost 2 as he complied an incredible ERA of 0.74 over 85 innings of work.

Born 10/26/26 in Arlington Heights, Illinois, the recently turned 83-year old Dick Bokelmann posted a career minor league mark of 66-51, with a 3.21 ERA, from 1947-54. He spent four partial years with the Buffs (1950-53) while spending part of that same time with the parent club St. Louis Cardinals (1951-53). Bokie’s Cardinals/Big League mark was 3-4 with a 4.90 ERA.

It is also true that it was two men, Houston Buff knuckleballers Al Papai and Dick Bokelmann, who prepared me to be a fan of Joe and Phil Niekro a few years later. It was an easy jump to make. I don’t think I’ve ever met a knuckleballer that I didn’t really like.Every one of them has been a remarkably individual and high integrity human being.

Iconic General Manager Branch Rickey of the St. Louis Cardinals had a three-pronged plan for helping himself. (1) He had a deal with club owner Sam Breadon. He got to keep a percentage of the net profits on the club’s operations, which meant, of course, that the less he paid out in personnel salaries, the more he got to keep for himself, as long as the club kept on winning. (2) He counted on the reserve clause and a loaded pipeline of talented players in the farm team system, players with no choice in baseball beyond the Cardinals, to keep him supplied with game-winning material. (3) He needed a few key people in the organization who were capable of doing more than one essential task at one time for the lowest salary he could work out with them for the price of a single employee’s salary.

Iconic General Manager Branch Rickey of the St. Louis Cardinals had a three-pronged plan for helping himself. (1) He had a deal with club owner Sam Breadon. He got to keep a percentage of the net profits on the club’s operations, which meant, of course, that the less he paid out in personnel salaries, the more he got to keep for himself, as long as the club kept on winning. (2) He counted on the reserve clause and a loaded pipeline of talented players in the farm team system, players with no choice in baseball beyond the Cardinals, to keep him supplied with game-winning material. (3) He needed a few key people in the organization who were capable of doing more than one essential task at one time for the lowest salary he could work out with them for the price of a single employee’s salary. seems that way. His 17-year minor league playing career (1930-41, 1946-48) as a pretty good hitting middle infielder, however, quickly revealed an even greater talent for leadership. At age 26, Keane was awarded his first managerial assignment from the parent Cardinals as Manager of the Class D Albany, Georgia Travelers. Johnny promptly rewarded the Rickey organization’s judgment of him by reeling off two consecutive first place league pennant winners in Albany in both 1938 and 1939.

seems that way. His 17-year minor league playing career (1930-41, 1946-48) as a pretty good hitting middle infielder, however, quickly revealed an even greater talent for leadership. At age 26, Keane was awarded his first managerial assignment from the parent Cardinals as Manager of the Class D Albany, Georgia Travelers. Johnny promptly rewarded the Rickey organization’s judgment of him by reeling off two consecutive first place league pennant winners in Albany in both 1938 and 1939. The six foot tall, 164 pound stringbean righthander named Jack Dalton Creel was born on April 23, 1915 in a little place called Kyle, Texas. From 1938 through 1953, Creel amassed a fifteen season record of 179 wins, 157 losses, and an earned run average of 3.37 Throw in the 5-4, 4.74 W-L, ERA record he recorded in his one 1945 season with the St. Louis Cardinals and you’re looking at a pretty fair country resume’ for a fellow who played it all out during one of baseball’s most heavily talented personnel eras.

The six foot tall, 164 pound stringbean righthander named Jack Dalton Creel was born on April 23, 1915 in a little place called Kyle, Texas. From 1938 through 1953, Creel amassed a fifteen season record of 179 wins, 157 losses, and an earned run average of 3.37 Throw in the 5-4, 4.74 W-L, ERA record he recorded in his one 1945 season with the St. Louis Cardinals and you’re looking at a pretty fair country resume’ for a fellow who played it all out during one of baseball’s most heavily talented personnel eras.

Houston Baseball”s two Hal Smths were always being confused for one another. It didn’t help clarity much that they played ball in the same era and, worse, that they played the same position and both batted right handed. I’ve forgotten how often the same statement would come up from different friends at games during the 1962 first seson of the Colt .45s: “Oh yeah,” they’d say, “I remember that guy at catcher, that Hal Smith. He played for the Buffs a few years back.”

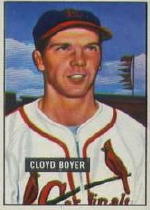

Houston Baseball”s two Hal Smths were always being confused for one another. It didn’t help clarity much that they played ball in the same era and, worse, that they played the same position and both batted right handed. I’ve forgotten how often the same statement would come up from different friends at games during the 1962 first seson of the Colt .45s: “Oh yeah,” they’d say, “I remember that guy at catcher, that Hal Smith. He played for the Buffs a few years back.” Cloyd Victor Boyer, Jr. was the eldest of three brothers who all played professional baseball up through the major league level. Born in Alba, MO on September 1, 1930, Cloyd pitched in parts of 14 minor league and 5 major league seasons from 1945 to 1961. Two of those seasons for the 6’1″, 188 lb. right hander included service with the 1948 (16-10, 3.15 ERA) and 1953 (4-2, 2.73) Houston Buff clubs. Boyer was a pitcher with a good variety of variable speed options and fair control. He gave up a lot of hits per game (8.6 per innings, career), but he also was effective in getting batters to put playable outs on the field. Over the course of his entire career, he won 137 games and lost 120, recording a minor league career ERA of 3.52. After his active career concluded, Cloyd managed in the minors on five scattered year occasions from 1963 through 1989. He then retired from baseball to his native area of southwestern Missouri.

Cloyd Victor Boyer, Jr. was the eldest of three brothers who all played professional baseball up through the major league level. Born in Alba, MO on September 1, 1930, Cloyd pitched in parts of 14 minor league and 5 major league seasons from 1945 to 1961. Two of those seasons for the 6’1″, 188 lb. right hander included service with the 1948 (16-10, 3.15 ERA) and 1953 (4-2, 2.73) Houston Buff clubs. Boyer was a pitcher with a good variety of variable speed options and fair control. He gave up a lot of hits per game (8.6 per innings, career), but he also was effective in getting batters to put playable outs on the field. Over the course of his entire career, he won 137 games and lost 120, recording a minor league career ERA of 3.52. After his active career concluded, Cloyd managed in the minors on five scattered year occasions from 1963 through 1989. He then retired from baseball to his native area of southwestern Missouri. The youngest of these three ballplaying brothers was Clete Boyer, who was born on 2/08/1937 in Cassville, MO. Clete was also a right handed hitting third baseman with superior defensive skills. When Clete and Ken faced off against each other in the 1964 World Series as rival third basemen for the Yankees and Cardinals, it was a mighty big day back in southwestern Missouri. – Clete played most of his career for the Yankees and Braves, finishing his major league career with a .242 BA and 162 HR (1955-71.) He never made it to Houston as a player for the Buffs, Colt .45s, or Astros, but we would have loved having him on our resume too.

The youngest of these three ballplaying brothers was Clete Boyer, who was born on 2/08/1937 in Cassville, MO. Clete was also a right handed hitting third baseman with superior defensive skills. When Clete and Ken faced off against each other in the 1964 World Series as rival third basemen for the Yankees and Cardinals, it was a mighty big day back in southwestern Missouri. – Clete played most of his career for the Yankees and Braves, finishing his major league career with a .242 BA and 162 HR (1955-71.) He never made it to Houston as a player for the Buffs, Colt .45s, or Astros, but we would have loved having him on our resume too.

That’s Houston Buffs President Allen Russell in the business suit and hat at the far left of today’s featured first photo. He’s showing some kind of report in early 1950 to St. Louis Cardinal coaches Runt Marr (next to Russell) and Freddy Hawn (far right). That’s Kemp Wicker, the first of two managers who commanded the Good Ship Buffalo at the start of the ’50 season wearing the “Houston” jersey. Little Benny Borgmann would soon replace Wicker and manage the Buffs for most of their ride into the Texas League cellar that most inglorious year, but that kind of field performance disaster never stopped Allen Russell. It simply provided a different kind of marketing challenge.

That’s Houston Buffs President Allen Russell in the business suit and hat at the far left of today’s featured first photo. He’s showing some kind of report in early 1950 to St. Louis Cardinal coaches Runt Marr (next to Russell) and Freddy Hawn (far right). That’s Kemp Wicker, the first of two managers who commanded the Good Ship Buffalo at the start of the ’50 season wearing the “Houston” jersey. Little Benny Borgmann would soon replace Wicker and manage the Buffs for most of their ride into the Texas League cellar that most inglorious year, but that kind of field performance disaster never stopped Allen Russell. It simply provided a different kind of marketing challenge. As modeled in the photo by the Buffs’ sluggung first baseman Jerry Witte, the Buffs agreed to wear shorts, as I also covered in a recent article. The ostensible reason given for this change was that the Buffs wanted to do all they could to make sure their players were made as comfortable as possible in the searing, humid Houston summer heat.

As modeled in the photo by the Buffs’ sluggung first baseman Jerry Witte, the Buffs agreed to wear shorts, as I also covered in a recent article. The ostensible reason given for this change was that the Buffs wanted to do all they could to make sure their players were made as comfortable as possible in the searing, humid Houston summer heat. In 1946, the year that Russell took over as Buffs President, the Buffs drew 161,000 fans and the major league St. Louis Browns drew 526,000. The very next year, 1947, the Buffs outdrew the Browns by 326,000 to 282,000. By 1948, the Buffs again won the gate battle, 401,000 to 336,000. The Browns edged a bad Buffs team in 1949 by 271,000 to 254,000, but an 8th places Buffs club in 1950 still edged a 7th place Browns club by 256.000 to 247,000. The Buffs won again in 1951 by 333,000 ro 294,000 By 1952, St. Louis was reaping the benefits of Bill Veeck’s second year at the Browns helm. The Browns outdrew the Buffs by 519,000 to 195,000 in 1952 – and they edged them again in 1953, the last year of the Browns, by a 297,000 to 204,000 count.

In 1946, the year that Russell took over as Buffs President, the Buffs drew 161,000 fans and the major league St. Louis Browns drew 526,000. The very next year, 1947, the Buffs outdrew the Browns by 326,000 to 282,000. By 1948, the Buffs again won the gate battle, 401,000 to 336,000. The Browns edged a bad Buffs team in 1949 by 271,000 to 254,000, but an 8th places Buffs club in 1950 still edged a 7th place Browns club by 256.000 to 247,000. The Buffs won again in 1951 by 333,000 ro 294,000 By 1952, St. Louis was reaping the benefits of Bill Veeck’s second year at the Browns helm. The Browns outdrew the Buffs by 519,000 to 195,000 in 1952 – and they edged them again in 1953, the last year of the Browns, by a 297,000 to 204,000 count.

By the time the young man from Sancti Spiritus, Cuba arrived here in 1951 as a member of the Houston Buffs pitching staff, the 26 year old righthander was already drawing favorable comparisons to the great big league Cuban hurler of the 1920s, Adolfo Luque of the Cincinnati Reds. Rubert had stormed onto the scene in 1946, going 13-6 with a 1.72 ERA for the Class C West Palm Beach club. – He then bettered that mark with the same team in 1947 by pumping his record up to 23-12 1ith a 1.76 ERA. Want more? Rubert went over to Class C Tampa in 1948 and pulled off a 22-7 record with a 2.11 ERA.

By the time the young man from Sancti Spiritus, Cuba arrived here in 1951 as a member of the Houston Buffs pitching staff, the 26 year old righthander was already drawing favorable comparisons to the great big league Cuban hurler of the 1920s, Adolfo Luque of the Cincinnati Reds. Rubert had stormed onto the scene in 1946, going 13-6 with a 1.72 ERA for the Class C West Palm Beach club. – He then bettered that mark with the same team in 1947 by pumping his record up to 23-12 1ith a 1.76 ERA. Want more? Rubert went over to Class C Tampa in 1948 and pulled off a 22-7 record with a 2.11 ERA. That’s “Black Mike” Clark and the bust of Eddie Kazak showing up in this cropping from a team photo – and they were just two of the guys who helped Octavio Rubert and the ’51 Buffs make their day in the baseball sun a mostly happy one. The party was only spoiled by Houston’s six-game loss to Birmingham in the Dixie Series. Our excuse? A mysterious stomach illness hospitalized Vinegar Bend Mizell and made him unavailable for the Buffs’ Series cause at crunch time.

That’s “Black Mike” Clark and the bust of Eddie Kazak showing up in this cropping from a team photo – and they were just two of the guys who helped Octavio Rubert and the ’51 Buffs make their day in the baseball sun a mostly happy one. The party was only spoiled by Houston’s six-game loss to Birmingham in the Dixie Series. Our excuse? A mysterious stomach illness hospitalized Vinegar Bend Mizell and made him unavailable for the Buffs’ Series cause at crunch time. The goal of every young and upcoming Houston Buff from 1923 through 1958 was to play well enough in the Texas League to either move up the following season to AAA ball, or even better, to do so well that that they went straight on up to the roster of the St. Louis Cardinals. I’m bracketing the era as 1923 through 1958 for one simple reason: That’s the time period in Buffs history in which the Cardinals either controlled or owned the futures of all ballplayers who passed through Houston professional baseball.

The goal of every young and upcoming Houston Buff from 1923 through 1958 was to play well enough in the Texas League to either move up the following season to AAA ball, or even better, to do so well that that they went straight on up to the roster of the St. Louis Cardinals. I’m bracketing the era as 1923 through 1958 for one simple reason: That’s the time period in Buffs history in which the Cardinals either controlled or owned the futures of all ballplayers who passed through Houston professional baseball.

The third man, Russell Rac, never got a single time at bat in the big leagues in spite of some pretty good hitting and fielding success with the Buffs in seven of his eleven season (1948-58) all minor league career. He began in Houston in 1948 – and he left as a Buff ten years later with a .312 season average, 12 homers, and 71 runs batted in for 1958. Few, if any, other players spent as many seasons as an active member of the Houston Buffs roster. Russell Rac went back to Galveston and into business from baseball following the 1958 season, where he continues to live in retirement as a man whose heart still belongs to baseball.

The third man, Russell Rac, never got a single time at bat in the big leagues in spite of some pretty good hitting and fielding success with the Buffs in seven of his eleven season (1948-58) all minor league career. He began in Houston in 1948 – and he left as a Buff ten years later with a .312 season average, 12 homers, and 71 runs batted in for 1958. Few, if any, other players spent as many seasons as an active member of the Houston Buffs roster. Russell Rac went back to Galveston and into business from baseball following the 1958 season, where he continues to live in retirement as a man whose heart still belongs to baseball.

The young man they were already calling Vinegar Bend Mizell arrived in Houston with the Buffs in the spring of 1951, heralded full bore as the lefthanded second coming of Dizzy Dean from twenty years earlier. Buff fans, sportswriters, club president Allen Russell, and the parent team St. Louis Cardinals all hoped the “Lil Abner Look-n-Sound-Alike” would turn out to be everything his growing legend screamed out that he was going to be: a sure-fire and consistent twenty game wins per season superstar and future Hall of Famer. Mizell wasn’t quite the young braggart that Dean had been, but he opened his mouth enough to create words that some writers ran to type as promises for use as future nails, should he fail to deliver.

The young man they were already calling Vinegar Bend Mizell arrived in Houston with the Buffs in the spring of 1951, heralded full bore as the lefthanded second coming of Dizzy Dean from twenty years earlier. Buff fans, sportswriters, club president Allen Russell, and the parent team St. Louis Cardinals all hoped the “Lil Abner Look-n-Sound-Alike” would turn out to be everything his growing legend screamed out that he was going to be: a sure-fire and consistent twenty game wins per season superstar and future Hall of Famer. Mizell wasn’t quite the young braggart that Dean had been, but he opened his mouth enough to create words that some writers ran to type as promises for use as future nails, should he fail to deliver. Mizell was critical to the success of Houston’s 1951 Texas League pennant drive, posting a 16-14 record that wasn’t altogether his fault on the short side of his wins to losses ratio. The club just had one of those seasons in which they often had trouble giving Mizell the offensive support he needed to take the win. His 1951 Earned Run Average of 1.96 still spoke volumes about his bright future as a prospect.

Mizell was critical to the success of Houston’s 1951 Texas League pennant drive, posting a 16-14 record that wasn’t altogether his fault on the short side of his wins to losses ratio. The club just had one of those seasons in which they often had trouble giving Mizell the offensive support he needed to take the win. His 1951 Earned Run Average of 1.96 still spoke volumes about his bright future as a prospect. I had the good fortune of finally meeting Wilmer David Mizell when we were seated together at the same table at the banquet hall for the Spetember 1995 “Last Round Up of the Houston Buffs.” I had a chance to ask him if the squirrel hunting story were true. “Did you like the story?” Mizell asked me in return?” “Oh yeah! I always loved it!” I told Mizell. “In that case, it was absolutely true!” Mizell shot back with a wink and a smile.

I had the good fortune of finally meeting Wilmer David Mizell when we were seated together at the same table at the banquet hall for the Spetember 1995 “Last Round Up of the Houston Buffs.” I had a chance to ask him if the squirrel hunting story were true. “Did you like the story?” Mizell asked me in return?” “Oh yeah! I always loved it!” I told Mizell. “In that case, it was absolutely true!” Mizell shot back with a wink and a smile.