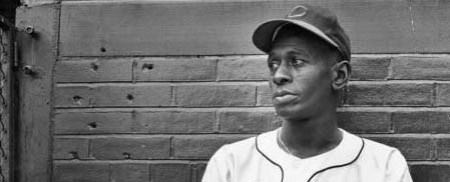

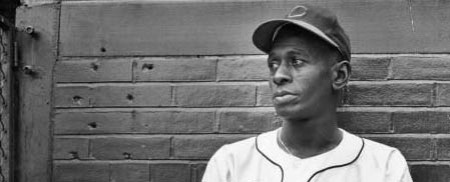

Satchel Paige was a long way from his 1933 stay in Bismarck, ND when this late 1960s Astrodome picture was taken.

As best we can know, Leroy “Satchel’ Paige had just turned age 27 on July 7th of the 1933 baseball season and he was already rattling the woods of Bismarck baseball with his loss to major league baseball to the level of racism that didn’t apply to the game-builders of North Dakota. Satch wasn’t driven by ego. He was more inclined to make his geographical moves on the wayward winds that blow into the souls of all those people who always get restless over time to check out what lays ahead on the other side of the mountain or down in the next valley somewhere.

In 1933, Satchel Paige did not feel the beckoning call of greater fame and opportunity that came with that invitation to pitch for the eastern Negro League all-stars at Comiskey Park in Chicago, so he turned it down to remain in the hills of North Dakota.

What a guy! Had there not been for that racist barrier known as the color line, Satchel Paige likely would have been a four to six-year MLB veteran by 1933, and facing off earlier that summer in the first big league all-star game as either a mound opponent or replacement for Carl Hubbell of the National League. In reality, Paige had to wait for the color line to fall before he got his first shot at the majors on June 9, 1948, two days after his 42nd birthday.

Here’s a brief capsule story on how things were going for young Satchel Paige in September 1933 from the pages of the Bismarck (ND) Tribune:

—————————————————————————————

Bismarck, North Dakota, September 9, 1933

BISMARCK BASEBALL NINE WILL END BASEBALL SEASON AT JAMESTOWN NEXT SUNDAY

SATCHEL PAIGE AND BARNEY BROWN ARE EXPECTED TO PITCH

———-

GREAT BATTLE IS FORECAST

———-

Local Colored Pitcher Turns Down Invitation to Pitch at Chicago

———-

Bismarck’s potent baseball club will end its season Sunday when it clashes with the strong Jamestown nine at the Stutsman county City.

The game is scheduled to begin at 3 o’clock according to Neil O. Churchill, manager of the Capitol City contingent.

Having turned down an invitation to pitch for the eastern colored all-stars in a World’s Fair feature game against the western all-stars at Comiskey Park, Chicago, Satchel Paige, elongated right hander, will take the field for Bismarck.

Satchel last Sunday climaxed his home stand here by out pitching Willie Roster (really “Foster”), left-hander who will hurl for the western all-stars at Chicago, as well as driving in all three runs in Bismarck’s 3-2 conquest of the Stutsman county crew in 10 innings.

Brown Probable Opponent

It is likely that Manager O.K. Butts of the Jamestown team will start Barney “Lefty” Brown, another colored southpaw star who is a great pitcher despite the fact that Bismarck drove him from the box in four innings Labor Day. Brown secured eight hits in twelve trips to the plate for an average of .666 in the three game series between Bismarck and Jamestown last weekend. ….

…. Bismarck Tribune, September 9, 1933, Page 6.

——————————————————————————————————–