The Ist Annual Knuckle Ball, a full dress benefit banquet established by the Joe Niekro Foundation to raise money for aneurysm research at Methodist Hospital in Houston, took place as scheduled on Friday night, July 31st, at Minute Maid Park. The gala dinner featured both a silent auction that filled the entire Union Station rotunda – and a live auction conducted by Stephen Lewis during the dinner itself.

The Ist Annual Knuckle Ball, a full dress benefit banquet established by the Joe Niekro Foundation to raise money for aneurysm research at Methodist Hospital in Houston, took place as scheduled on Friday night, July 31st, at Minute Maid Park. The gala dinner featured both a silent auction that filled the entire Union Station rotunda – and a live auction conducted by Stephen Lewis during the dinner itself.

With Hall of Famer Joe Morgan serving as master of ceremonies, the attending guest list read like the Who’s Who of baseball – and with a pretty good taste of some big lights in the sports of football, basketball, and soccer making roll call too. For an effort started by a great boost of energy and intelligence from Joe’s daughter, Natalie Niekro, the program unfolded as an equal tribute to both Joe ad Natalie. It took all of the Niekro family intelligence and determination, clicking on all cylinders, to come off as well as it did – and it came off very, very well.

In addition to Joe Morgan, other Baseball Hall of Famers on hand included Joe’s brother Phil Niekro, of course, Sparky Anderson, Bob Feller, Robin Roberts, and Ozzie Smith. (Forgive me if I left anyone out.) The list of famous former Houston Astros was equally impressive, but here’s where I know I’m going to miss some names. There were just too many former Colt .45’s and Astros circulating among the crowd of several hundred people who came on this special night for absolute certainty here, but this is my humble list of countable people: Kevin Bass, Dave Bergman, Enos Cabell, Larry Dierker, Phil Garner, Ed Herrmann, Art Howe, Craig Reynolds, Joe Sambito, Mike Scott, Bill Virdon, Carl Warwick, and Jimmy Wynn. And that Astros list is expanded importantly too by the additions of Owner/CEO Drayton McLane, Baseball President Tal Smith, Business President Pam Gardner, General Manager Ed Wade, and longtime loyal Astros employee Judy Veno. Longtime media folks like Kenny Hand and Gina Gaston of Channel 13 were also present, as were Jo Russell, the widow of former Buffs President Allen Russell, Larry Dluhy of the Texas Baseball Hall of Fame, and spiritual writer and teacher Marie Wynn. Other sport icons in attendance inluded former Houston Rocket and Basketball Hall of Famer Elvin Hayes, former Houston Rocket star Mario Elle, former Houston Oiler quarterback Dan Pastorini, and former Oiler quarterback Oliver Luck, who now also happens to be President of the Houston Dynamo, the city’s first serious venture into the world of professional soccer. Former Pirate-Tiger Jim Foor and his terrrific wife Sandy Foor were also present to make everything shine all the more. Jim and Sandy have both logged time as playing members of our Houston Babies vintage base ball club as charter members of the 21st century edition of Houston’s 1888 original pro club. Other Babies players in attendance included Jimmy Disch, Scott Disch, Matt Moak, Logan Greer, and yours truly, Bill McCurdy, the Babies General Manager. – Satch and Lynn Davidson also were on hand. Satch Davidson is a former National League umpire and a member of the Texas Baseball Hall of Fame; Lynn Davidson, of course, is the well-known and respected Houston pet bereavement professional.

The reception began officially at 6:36 PM. The past normal time start was done to (1) highlight Joe Niekro’s uniform number as an Astro; and (2) to also make the point that it is now past time, via Joe’s decesased status, to consider retiring his Houston uniform number 36 from all service use by any future Astros. Among all his many accomplishments in baseball, Joe Niekro has held onto one very special record in Houston MLB franchise history. – With 144 wins in Houston, Joe Niekro has the most career victories as a Houston big league pitcher – and he has held that record since 1985, when he passed Larry Dierker for that distinction. Dierker remains second to Niekro in career Houston wins with 137, but current Astro ace Roy Oswalt (with 135 wins) is on course to pass both Dierker and Niekro sometime in the 2010 season, barring, heaven forbid, any further complications that may linger into 2010 from his current disk troubles. One thing this likely means is that Joe Niekro most probably will have surrendered a great Houston record next season – but only after holding onto it for a quarter century (1985-2010).

Thousands of us ancient fans of both Joe Niekro and the Astros think it’s high time now to honor the man for all he has meant and continues to mean to this franchise and the quality of life in Houston. The Joe Niekro Foundation and the Knuckle Ball stand tall as living proof of the Nielro family commitment to Houston. Let’s retire # 36 at Minute Maid Park in Joe Niekro’s honor during the time, or coincidant with the time, that current pitching star Roy Oswalt closes in and becomes the new record-holder next season. Such a ceremony at MMP will pack the house – and rightly so. I cannot think of another move the Astros could make in this area that would be more deservedly supported by the fans. As a man of performace and character, no one else out there on the cusp of receiving this special club action of honor holds even a small candle to Joe Niekro as an equally deserving recipient. – That grail belongs to Joe Niekro. – So, let’s give it to him – and by no later than 2010, please. It’s the intelligent, tuned-in, right thing to do.

Til then, the music plays on, – and there were all kinds of musically soaring spirits going on at Friday night’s electric Knuckle Ball. The Houston Astros are to be congratulated for lending their magnificent facilities to the cause as the most fitting venue for this banquet celebration of Joe Niekro’s life. Everything that everyone saw and experienced on the broad ban of things worked out beautifully. Special applause goes out to Drayton McLane in this regard too. The man’s support of things that are good for Houston fly too far beneath the radar. It is time that people started recognizing that we have a club owner in Houston who shows his caring for happens in this community in ways that count. I’ll start the line here by saying, “Thank you, Drayton! You are, without a doubt, the good man that your daddy raised you to be – and we appreciate you! The Knuckle Ball could not have succeeded on its high level this first year, and under these economic conditions, had it not been for you and your people. – Houston thanks you!”

The evening program following the reception began with a delicious meal and a heartwarmig welcome and explanation from Natalie Niekro about how the Joe Niekro Foundation and the Knuckle Ball came to be as a “Pitch for Life” against the sudden silent killer that is aneurysm. Natalie was followed by one of her dad’s former Astros teammates, Enos Cabell, who spoke of what it meant personally to have known Joe Niekro as a fellow player and friend.

I shared a table with several wonderfully knowledgeable Houston people, including Hal Finberg and Marc Melcher of the Global Wealth Management, Merrill Lynch team. Hal kept us posted at the banquet on the Astros@Cardinals scores from St. Louis, and Marc shared some interesting news of the Heritage Society’s plans to stage a major show next year on the history of baseball in Houston. Marc Melcher serves on their board. Hmmm! I wonder if I know of anyone who might enjoy getting involved in that project? – Now, how in the world did Marc and I happen to find ourselves seated next to each other by “accident?”

The old age jokes were flying high in my neighborhood on Friday night. Jim Foor enjoyed introducing me as the original and only General Manager of the Houston Babies. – The Babies played their first game on March 6, 1888! – Later on, Dave Bergman and Ed Herrmann stopped by to speak with me as we were waiting on our cars in the valet parking pickup line. They each wanted to tell me how much they enjoyed my poem about Joe Niekro, but Ed Herrmann acted as though he didn’t expect to be remembered. “I remember you, Ed,” I said. “You were a catcher.” Herrmann got this stunned look on his face as I said these words, but before either of us could speak again, former first baseman Bergman chirped in with, “See there, Ed! I told you if you just came with me tonight that we’d eventually run into somebody who was old enough to remember you!”

What great fun we all had – and all for a worthy cause too!

Music at the end of the evening’s program was provided by Grammy Award Country Music Artist Collin Raye.

My role on this magic Friday was to recite a poem that I had written about Joe Niekro and the new Knuckle Ball purpose. I was there by special invitation from Ms. Niekro. Although I did not read the title on Friday night, I’m calling this piece “A Pitch for Life Against Sudden Death.” I’m just happy that I was able to get through my recitation without tongue-tripping over my own material before this once-in-a-lifetime audience. Here’s the copy – without the spoken voice breaks and pauses that breathe it completely into life:

Born in Martins Ferry – in the fall of ’44, Joe and Brother Phil – were the knuckler’s paramour! – They wound their way through baseball, vexing hitters all the same – From Mendoza’s line to Da Vinci’s circle, the knuckler was to blame!

Born in Martins Ferry – in the fall of ’44, Joe and Brother Phil – were the knuckler’s paramour! – They wound their way through baseball, vexing hitters all the same – From Mendoza’s line to Da Vinci’s circle, the knuckler was to blame!

A batter couldn’t hit a pitch that floated, dipped, and dove. – He simply left his hopes stillborn, back on the old hot stove. – The Niekros didn’t waver; their pitches danced and sang. – They stung their foes with K’s and woes; the victory bell they rang!

Three-hundred Eighteen wins for Phil; Two Twenty-One for Joe! – Phil found his way to Cooperstown; Joe’s glory came too, you know! – In 2005, Joe Niekro, – for his Astros heart, so game, – Was proudly too inducted by the Texas Hall of Fame!

And when we lost sweet Joseph – in October of ’06, – There were no words to heal the shock of a loss that so transfixed, – Our attention to the cause of loss – aneurysm was its name, – And wiping out that assassin is the Knuckle Ball’s lone game!

And as we think of Joseph now – as we surely always will, – We shall always think of him and Phil – and all they did to thrill, – The hearts of baseball fantasy – that rode the knuckler wave, – One as a loyal Astro – the other as a mighty Brave!

And as we say hello again to a baseball summer night, – We shall not see a sky with stars that does not soon invite, – All our fondest memories of the knuckler – and the man, – Ascending all around us! – Count the diamonds, if you can!

Go forth, Joeseph Niekro, through the heavens afar! – Throw your tantalizing knuckler, so we’ll know where you are! – And, on some summer night soon, across a sky, black as tar, – We shall find you fluttering wobblers, striking out a shooting star!

Go forth, Joeseph Niekro, through the heavens afar! – Throw your tantalizing knuckler, so we’ll know where you are! – And, on some summer night soon, across a sky, black as tar, – We shall find you fluttering wobblers, striking out a shooting star!

And every time we find you again, our prayer shall be simple, but true: – “Lead us in the Knuckle Ball pitch, Joe, for an answer to aneurysm too!” – The silent monster must be slain; the resident villain must be banned! – We shall not rest until the day – there are cures for the evil at hand!

So, go forth for us all, Joe Niekro, through the infinite heavens afar! – Throw your tantalizing knuckler again, so we’ll know where you are! – And on some summer night soon, across a sky pitch-black as tar, – We shall find you fluttering wobblers, striking out a shooting star!

We can do it with your help, Joe! – You’re pitching in the Bigger League now!

We just returned last night from a two-day train trip to Lake Charles, but that’s a story for another day. This morning I want to tell you about another ex-Cardinal and former Buff pitcher who also just happened to be a good friend. His name was George “Red” Munger, a name that won’t be lost to the memories of anyone who was around during all those 1940s years of great Cardinal teams. Red Munger just happened to be a big part of that success. The native Houstonian and lifelong East Ender was smack dab in the middle of that zenith era in Cardinal history, even though he lost all of 1945 and most of the championship 1946 season to military service. Red still managed to return in time to make his own contributions to the Cardinals’ victory over the Boston Red Sox in the 1946 World Series.

We just returned last night from a two-day train trip to Lake Charles, but that’s a story for another day. This morning I want to tell you about another ex-Cardinal and former Buff pitcher who also just happened to be a good friend. His name was George “Red” Munger, a name that won’t be lost to the memories of anyone who was around during all those 1940s years of great Cardinal teams. Red Munger just happened to be a big part of that success. The native Houstonian and lifelong East Ender was smack dab in the middle of that zenith era in Cardinal history, even though he lost all of 1945 and most of the championship 1946 season to military service. Red still managed to return in time to make his own contributions to the Cardinals’ victory over the Boston Red Sox in the 1946 World Series. achieved some great, but unsurprising success in service baseball. He was just too good for the competition he faced at that rank amateur level. Once Red obtained his second lieutenant’s commission and was assigned to developing the baseball program at his base in Germany, he just stopped playing in favor of full time teaching. He even said that he had no heart for pitching or hitting against competitors who were too young, too green, and too unable to compete against him.

achieved some great, but unsurprising success in service baseball. He was just too good for the competition he faced at that rank amateur level. Once Red obtained his second lieutenant’s commission and was assigned to developing the baseball program at his base in Germany, he just stopped playing in favor of full time teaching. He even said that he had no heart for pitching or hitting against competitors who were too young, too green, and too unable to compete against him. After baseball, Red Munger worked as a minor league pitching coach and also as a private investigator for the Pinkerton agency. He later developed diabetes and passed away from us on July 23, 1996 at age 77. I took that last picture of him in the 1946 Cardinals replica cap on a visit to his home, about two weeks before he died. Red gave me that cap that he wore in the picture at left on the same day. I have treasured it ever since.

After baseball, Red Munger worked as a minor league pitching coach and also as a private investigator for the Pinkerton agency. He later developed diabetes and passed away from us on July 23, 1996 at age 77. I took that last picture of him in the 1946 Cardinals replica cap on a visit to his home, about two weeks before he died. Red gave me that cap that he wore in the picture at left on the same day. I have treasured it ever since. Red Munger enjoyed watching position players with strong arms and then imagining how effective they might be as pitchers. His favorite subject that last summer of 1996 was Ken Caminiti – and this was long before all the disclosures about Ken’s mind-altering and performace-enhancing drug abuse. Red Munger just liked the man as a gifted athlete. Caminiti fit the bill on what Red Munger was looking for in pitching potential. “Give me a guy with a strong arm and I can probably teach him the other things he needs to know about pitching. I can’t teach a guy how to have a strong arm – and as far as I can see, no one else can do that either beyond telling him to work out and hope for the best. As far as I’m concerned in the matter of good arms, you’ve either got one or you don’t.”

Red Munger enjoyed watching position players with strong arms and then imagining how effective they might be as pitchers. His favorite subject that last summer of 1996 was Ken Caminiti – and this was long before all the disclosures about Ken’s mind-altering and performace-enhancing drug abuse. Red Munger just liked the man as a gifted athlete. Caminiti fit the bill on what Red Munger was looking for in pitching potential. “Give me a guy with a strong arm and I can probably teach him the other things he needs to know about pitching. I can’t teach a guy how to have a strong arm – and as far as I can see, no one else can do that either beyond telling him to work out and hope for the best. As far as I’m concerned in the matter of good arms, you’ve either got one or you don’t.” His name was Paul Boesch. By the time the 35-year old Brooklyn native reached Houston in 1947, he had already lived the fullest life of a great adventurer and real life hero. Born on October 2, 1912, this son of a New York street car conductor was one of seven children. When his father died before Paul reached age 5, the business of survival fell upon his mother and older siblings. His mother worked as a domestic servant to well-to-do families and the struggling Boesch household survived. Graduating from high school in 1929, according to one report, young Paul Boesch soon found excellence in his pursuit of achievements that required a combination of mental and physical skills. In 1932, he placed third in the highly regarded North Atlantic Coast Lifeguard Competition. Paul soon followed that success by choosing to join professional wrestling as his career. It was a choice that eventually led him to a 2005 posthumous induction into the Wrestling Hall of Fame.

His name was Paul Boesch. By the time the 35-year old Brooklyn native reached Houston in 1947, he had already lived the fullest life of a great adventurer and real life hero. Born on October 2, 1912, this son of a New York street car conductor was one of seven children. When his father died before Paul reached age 5, the business of survival fell upon his mother and older siblings. His mother worked as a domestic servant to well-to-do families and the struggling Boesch household survived. Graduating from high school in 1929, according to one report, young Paul Boesch soon found excellence in his pursuit of achievements that required a combination of mental and physical skills. In 1932, he placed third in the highly regarded North Atlantic Coast Lifeguard Competition. Paul soon followed that success by choosing to join professional wrestling as his career. It was a choice that eventually led him to a 2005 posthumous induction into the Wrestling Hall of Fame. Some reports say that Paul didn’t even finish high school, but whatever the case, his education on physical and emotional survival in a difficult world was far superior to that of most kids who grew up back then with the full protection of two stable parents. He began working as a lifeguard on the Alantic Coast by age 14. Over the course of his mostly adolescent career in that field, he was credited with saving about five hundred lives.

Some reports say that Paul didn’t even finish high school, but whatever the case, his education on physical and emotional survival in a difficult world was far superior to that of most kids who grew up back then with the full protection of two stable parents. He began working as a lifeguard on the Alantic Coast by age 14. Over the course of his mostly adolescent career in that field, he was credited with saving about five hundred lives. Paul Boesch returned to wrestling after World War II, but that all ended with a near fatal car crash in 1947 that combined with old back injuries from wrestling to effectively end his active career. He would still appear infrequently in grudge matches over the years, but the damage from the wreck removed him from full-time wrestling.

Paul Boesch returned to wrestling after World War II, but that all ended with a near fatal car crash in 1947 that combined with old back injuries from wrestling to effectively end his active career. He would still appear infrequently in grudge matches over the years, but the damage from the wreck removed him from full-time wrestling. Paul Boesch took to TV like honey sticks to peanut butter. After Morris Sigel died, Paul Boesch took his place as the local promoter of wrestling at the City Auditorium while continuing as the creative director of all the “good guy / bad guy” melodrama matches through his television broadcasts and wrestler interviews. When they tore the auditorium down in the mid-1960s and replaced it with Jones Hall, wrestling moved to the Sam Houston Coliseum and Boesch went with it. Paul Boesch and Houston Wrestling were continuously on the air from 1949 through 1989, mostly on Channel 39, although Boesch had to retire from broadcasting in 1987 due to a heart condition. On March 7, 1989, the gentle man with cauliflower ears passed away, leaving Houston and all the children’s charities he supported the poorer for it.

Paul Boesch took to TV like honey sticks to peanut butter. After Morris Sigel died, Paul Boesch took his place as the local promoter of wrestling at the City Auditorium while continuing as the creative director of all the “good guy / bad guy” melodrama matches through his television broadcasts and wrestler interviews. When they tore the auditorium down in the mid-1960s and replaced it with Jones Hall, wrestling moved to the Sam Houston Coliseum and Boesch went with it. Paul Boesch and Houston Wrestling were continuously on the air from 1949 through 1989, mostly on Channel 39, although Boesch had to retire from broadcasting in 1987 due to a heart condition. On March 7, 1989, the gentle man with cauliflower ears passed away, leaving Houston and all the children’s charities he supported the poorer for it. Paul Boesch was an anomaly. He was a genuine man of character – building a life on a stage that was totally sports fiction. Only the injuries and the knuckle-peppered cauliflower ears were firmly real in wrestling, but Paul Boesch was the “real deal” as a great and giving human being to the very core of his soul. The stuff he did for the neglected kids of Houston was legendary. And Houston lost a class act when this man passed from our midst.

Paul Boesch was an anomaly. He was a genuine man of character – building a life on a stage that was totally sports fiction. Only the injuries and the knuckle-peppered cauliflower ears were firmly real in wrestling, but Paul Boesch was the “real deal” as a great and giving human being to the very core of his soul. The stuff he did for the neglected kids of Houston was legendary. And Houston lost a class act when this man passed from our midst. Televised baseball “ain’t” what it used to be – thank goodness! Ten years after the first televised big league game from Ebbets Field in Brooklyn in 1939, KLEE-TV, Channel 2 in Houston, our only televison station then operating locally during the pre-coaxial cable days introduced the first viewing of baseball to the few Houstonians who owned those early 10 inch screen console receving sets that sold for about $400 at places like the Bayne Appliance Store. That was a lot of money for a family to pay for television back in 1949, but it was Houston’s first year with the new medium and there were then, as now, people with both the money and ego that were large enough to buy one at the early inflated price. There were no easy credit line purchases back in the day.

Televised baseball “ain’t” what it used to be – thank goodness! Ten years after the first televised big league game from Ebbets Field in Brooklyn in 1939, KLEE-TV, Channel 2 in Houston, our only televison station then operating locally during the pre-coaxial cable days introduced the first viewing of baseball to the few Houstonians who owned those early 10 inch screen console receving sets that sold for about $400 at places like the Bayne Appliance Store. That was a lot of money for a family to pay for television back in 1949, but it was Houston’s first year with the new medium and there were then, as now, people with both the money and ego that were large enough to buy one at the early inflated price. There were no easy credit line purchases back in the day. Bill Newkirk handled the first televised play-by-play at Buff Stadium of 1949 Houston Buffs games. He was assisted by longtime Buff, Colt .45, and Astro engineer Bob Green in generating those early productions. Newkirk was succeeded in 1950 by Dick Gottlieb of Channel 2, which by its second year had now been purchased by the William P. Hobby family and re-christened as KPRC-TV. Guy Savage, later of KTRK-TV Sports, Channel 13, also handled the play-by-play on a number of those early baseball telecasts from Buff Stadium.

Bill Newkirk handled the first televised play-by-play at Buff Stadium of 1949 Houston Buffs games. He was assisted by longtime Buff, Colt .45, and Astro engineer Bob Green in generating those early productions. Newkirk was succeeded in 1950 by Dick Gottlieb of Channel 2, which by its second year had now been purchased by the William P. Hobby family and re-christened as KPRC-TV. Guy Savage, later of KTRK-TV Sports, Channel 13, also handled the play-by-play on a number of those early baseball telecasts from Buff Stadium. BASEBALL FILM FESTIVAL IN WAXAHACHIE THIS WEEKEND, AUG. 14-16. Thanks to vintage 19th century base ballist Wendel Dickason, we are now advised of a benefit baseball film festival that is scheduled for the classic Tower Theatre in Waxahachie, Texas this coming Friday through Sunday, August 14-16. Proceeds from the event are all dedicated to the support of the Waxahachie High Shool baseball team.

BASEBALL FILM FESTIVAL IN WAXAHACHIE THIS WEEKEND, AUG. 14-16. Thanks to vintage 19th century base ballist Wendel Dickason, we are now advised of a benefit baseball film festival that is scheduled for the classic Tower Theatre in Waxahachie, Texas this coming Friday through Sunday, August 14-16. Proceeds from the event are all dedicated to the support of the Waxahachie High Shool baseball team. Ten seasons deep into its life as a baseball venue, the place that began as Enron Field at Union Station before its reputationally redemptive transformation into Astros Park, and then Minute Maid Park, is alive and well – and building surface patina by the layers-worth on its quirkiness as yet another one-of–a-kind home to Houston baseball. That tradition of uniqueness in Houston is steeped in the six major parks that have served as home to our professional baseball warriors since 1888.

Ten seasons deep into its life as a baseball venue, the place that began as Enron Field at Union Station before its reputationally redemptive transformation into Astros Park, and then Minute Maid Park, is alive and well – and building surface patina by the layers-worth on its quirkiness as yet another one-of–a-kind home to Houston baseball. That tradition of uniqueness in Houston is steeped in the six major parks that have served as home to our professional baseball warriors since 1888. 2) West End Park (1907-1927). For twenty-one seasons, for sure, the 2,500 seat wooden grandstand ballpark near downtown served as the home of the Houston Buffaloes of the Texas League. Rookie Buffs center fielder Tris Speaker helped cristen the place in 1907 with some dazzling play in the cavernous outfield while also leading the Texas League in hitting that year with a .314 batting average. During this same two-decade period, a young man from Austin named Fred Ankenman gradually took over running the Buffalo stampede into local hearts as chief executive under local ownership and later as President under the club’s ownership from the early 1920s by the major league St. Louis Cardinals. West End Park was a nice place, but it was never big enough to house the future plans of the fellow that ran the Cardinal operation – a fellow named Branch Rickey, the man who served as the genius of minor league farm team design and hands-on micromanager of all moves pertaining to Cardinals baseball. After the Cards won their first World Series over the New York Yankees in 1926, Rickey and Ankenman acquired a parcel of land on the rail lines that flowed east from downtown Houston. They built a $400,000 jewel of a ballpark on what was then called St. Bernard Avenue. That street later was renamed as Cullen Boulevard. The ballpark they built there was christened as Buffalo Stadium on April 11. 1928. Ironically, Union Station, at the corner of Texas and Crawford, was one of the principle places that fans caught the trains and street cars for transportation in the afternoons to Buffalo Stadium on game days.

2) West End Park (1907-1927). For twenty-one seasons, for sure, the 2,500 seat wooden grandstand ballpark near downtown served as the home of the Houston Buffaloes of the Texas League. Rookie Buffs center fielder Tris Speaker helped cristen the place in 1907 with some dazzling play in the cavernous outfield while also leading the Texas League in hitting that year with a .314 batting average. During this same two-decade period, a young man from Austin named Fred Ankenman gradually took over running the Buffalo stampede into local hearts as chief executive under local ownership and later as President under the club’s ownership from the early 1920s by the major league St. Louis Cardinals. West End Park was a nice place, but it was never big enough to house the future plans of the fellow that ran the Cardinal operation – a fellow named Branch Rickey, the man who served as the genius of minor league farm team design and hands-on micromanager of all moves pertaining to Cardinals baseball. After the Cards won their first World Series over the New York Yankees in 1926, Rickey and Ankenman acquired a parcel of land on the rail lines that flowed east from downtown Houston. They built a $400,000 jewel of a ballpark on what was then called St. Bernard Avenue. That street later was renamed as Cullen Boulevard. The ballpark they built there was christened as Buffalo Stadium on April 11. 1928. Ironically, Union Station, at the corner of Texas and Crawford, was one of the principle places that fans caught the trains and street cars for transportation in the afternoons to Buffalo Stadium on game days. 3) Buffalo/Buff Stadium (1928-1952); Busch Stadium (1953-1961). Subtract the three lost years in which the Texas League was closed down during World War II (1943-45) and “Buff Stadium” was home to Houston baseball for 31 active seasons from 1928 to 1961. I’m, of course, absorbing those few final seasons in which the place was technically renamed as “Busch Stadium” into that figure. Most of us diehard Buff fans never accepted that name change in the first place.

3) Buffalo/Buff Stadium (1928-1952); Busch Stadium (1953-1961). Subtract the three lost years in which the Texas League was closed down during World War II (1943-45) and “Buff Stadium” was home to Houston baseball for 31 active seasons from 1928 to 1961. I’m, of course, absorbing those few final seasons in which the place was technically renamed as “Busch Stadium” into that figure. Most of us diehard Buff fans never accepted that name change in the first place. 4) Colt Stadium (1962-64). It was never intended as anything more than service as a temporary home for Houston’sn new major league club, the Colt .45’s – and it’s just as well. The place that many of fans called “The Skillet” was tough enough during the work week night games, when Houston’s vampire squad mosquitoes feasted upon this congregation of human flesh and blood, but it was worse than Dante’s Inferno on weekends under the direct fiery blaze of the sun. With no overhead protection, and with the surrounding parking cement reflecting all that heat back up into the humidor-like confines of Colt Stadium, people dropped like flies at daytime weekend games. For those conditions, the short-lived Colt Stadium earned a place in baseball history. It forced the ball club to seek permission for night baseball on Sundays, something that had been unheard of previously due to all the blue law notions about the role of baseball on the Lord’s Day, anyway. Attedance at Sunday night games in Houston was so improved that it led to other clubs playing games at that night time slot also. It wasn’t long before televised Sunday Night Baseball became a fixture among the viewing habits of fans.

4) Colt Stadium (1962-64). It was never intended as anything more than service as a temporary home for Houston’sn new major league club, the Colt .45’s – and it’s just as well. The place that many of fans called “The Skillet” was tough enough during the work week night games, when Houston’s vampire squad mosquitoes feasted upon this congregation of human flesh and blood, but it was worse than Dante’s Inferno on weekends under the direct fiery blaze of the sun. With no overhead protection, and with the surrounding parking cement reflecting all that heat back up into the humidor-like confines of Colt Stadium, people dropped like flies at daytime weekend games. For those conditions, the short-lived Colt Stadium earned a place in baseball history. It forced the ball club to seek permission for night baseball on Sundays, something that had been unheard of previously due to all the blue law notions about the role of baseball on the Lord’s Day, anyway. Attedance at Sunday night games in Houston was so improved that it led to other clubs playing games at that night time slot also. It wasn’t long before televised Sunday Night Baseball became a fixture among the viewing habits of fans. 5) The Astrodome (1965-1999). Judge Roy Hofheinz dubbed it as ” the eighth wonder of the world” once he renamed the Harris County Domed Stadium as “The Astrodome” – the new home of the newly renamed Houston Astros. Looking back now, I have to admit to something that I think almost all of us experienced back then in those more innocent and far less jaded days of big change. – The idea of a domed stadium just blew us all away. We could not imagine any ballpark that could be built to protect the game from weather – that wouldn’t also interfere with the flight of most high-arching fly balls.

5) The Astrodome (1965-1999). Judge Roy Hofheinz dubbed it as ” the eighth wonder of the world” once he renamed the Harris County Domed Stadium as “The Astrodome” – the new home of the newly renamed Houston Astros. Looking back now, I have to admit to something that I think almost all of us experienced back then in those more innocent and far less jaded days of big change. – The idea of a domed stadium just blew us all away. We could not imagine any ballpark that could be built to protect the game from weather – that wouldn’t also interfere with the flight of most high-arching fly balls.

Minute Maid Park is a monument to baseball uniqueness among all other sports. As many fine writers have pointed out, ad nauseum, baseball isn’t controlled by the clock. Theoretically, a game could go on from here to eternity, if the score remains tied at the end of each full inning. It also doesn’t play out on an even gridiron, as does football. Baseball plays out on whatever field fits the reality of the community it serves – and you cannot blame your losses on the field of battle – unless you are just a loser looking for another easy excuse for your own failures.

Minute Maid Park is a monument to baseball uniqueness among all other sports. As many fine writers have pointed out, ad nauseum, baseball isn’t controlled by the clock. Theoretically, a game could go on from here to eternity, if the score remains tied at the end of each full inning. It also doesn’t play out on an even gridiron, as does football. Baseball plays out on whatever field fits the reality of the community it serves – and you cannot blame your losses on the field of battle – unless you are just a loser looking for another easy excuse for your own failures. When a pitcher goes through a season garnering 25 wins against only 8 losses, you have to figure that he’s speaking loud enough alone by his performance on the field. Well, that was exactly how the soft-spoken Clarence Beers played it as the pitching ace of the 1947 Houstons Buffs. His efforts, with some considerable help from the ’47 Buffs offense, plus fellow 20-game winner Al Papai, proved plentiful enough in getting the job done. With good command of his several quality pitches, the cool-tempered 28-year old quiet man from El Dorado, Kansas had done more than enough to draw attention from the parent club St. Louis Cardinals when it came to thinking about 1948 season. Beers had been a late season call up for the Buffs in 1940, but he only got here long enough at age 22 to go 0-1. Now it was seven years later, but even at age 29, and in spite of the fact that his 25-game win season in 1947 was only the first 20 plus wins year since his career began back 1n 1937, Clarence Beers finally had earned a shot at the majors with the Cards.

When a pitcher goes through a season garnering 25 wins against only 8 losses, you have to figure that he’s speaking loud enough alone by his performance on the field. Well, that was exactly how the soft-spoken Clarence Beers played it as the pitching ace of the 1947 Houstons Buffs. His efforts, with some considerable help from the ’47 Buffs offense, plus fellow 20-game winner Al Papai, proved plentiful enough in getting the job done. With good command of his several quality pitches, the cool-tempered 28-year old quiet man from El Dorado, Kansas had done more than enough to draw attention from the parent club St. Louis Cardinals when it came to thinking about 1948 season. Beers had been a late season call up for the Buffs in 1940, but he only got here long enough at age 22 to go 0-1. Now it was seven years later, but even at age 29, and in spite of the fact that his 25-game win season in 1947 was only the first 20 plus wins year since his career began back 1n 1937, Clarence Beers finally had earned a shot at the majors with the Cards. It’s hard to find a good picture of fellows like Guy Sturdy, almost as hard as finding anyone other than the most arcane-interested of baseball researchers who even remember him. That’s Guy Sturdy in the St. Louis Cardinalesque uniform of the 1935 Baltimore Orioles. Guy had taken over as manager of the then AA International League Orioles in late 1934. He held onto the skipper’s job without much success until he was fired and replaced during the 1937 season. Based upon Baltimore’s 5th place finish, 13 games back in 1935, we are inclined to presume that the new Packard that Sturdy is receiving in the picture as a gift from fans must have taken place at an earlier, more wishful moment near Opening Day of that season.

It’s hard to find a good picture of fellows like Guy Sturdy, almost as hard as finding anyone other than the most arcane-interested of baseball researchers who even remember him. That’s Guy Sturdy in the St. Louis Cardinalesque uniform of the 1935 Baltimore Orioles. Guy had taken over as manager of the then AA International League Orioles in late 1934. He held onto the skipper’s job without much success until he was fired and replaced during the 1937 season. Based upon Baltimore’s 5th place finish, 13 games back in 1935, we are inclined to presume that the new Packard that Sturdy is receiving in the picture as a gift from fans must have taken place at an earlier, more wishful moment near Opening Day of that season.

The Ist Annual Knuckle Ball, a full dress benefit banquet established by the Joe Niekro Foundation to raise money for aneurysm research at Methodist Hospital in Houston, took place as scheduled on Friday night, July 31st, at Minute Maid Park. The gala dinner featured both a silent auction that filled the entire Union Station rotunda – and a live auction conducted by Stephen Lewis during the dinner itself.

The Ist Annual Knuckle Ball, a full dress benefit banquet established by the Joe Niekro Foundation to raise money for aneurysm research at Methodist Hospital in Houston, took place as scheduled on Friday night, July 31st, at Minute Maid Park. The gala dinner featured both a silent auction that filled the entire Union Station rotunda – and a live auction conducted by Stephen Lewis during the dinner itself. Born in Martins Ferry – in the fall of ’44, Joe and Brother Phil – were the knuckler’s paramour! – They wound their way through baseball, vexing hitters all the same – From Mendoza’s line to Da Vinci’s circle, the knuckler was to blame!

Born in Martins Ferry – in the fall of ’44, Joe and Brother Phil – were the knuckler’s paramour! – They wound their way through baseball, vexing hitters all the same – From Mendoza’s line to Da Vinci’s circle, the knuckler was to blame! Go forth, Joeseph Niekro, through the heavens afar! – Throw your tantalizing knuckler, so we’ll know where you are! – And, on some summer night soon, across a sky, black as tar, – We shall find you fluttering wobblers, striking out a shooting star!

Go forth, Joeseph Niekro, through the heavens afar! – Throw your tantalizing knuckler, so we’ll know where you are! – And, on some summer night soon, across a sky, black as tar, – We shall find you fluttering wobblers, striking out a shooting star! A couple of days ago, I presented y choices for the All Time Buffs team, based upon career performances in the big leagues and their accomplishments with Houston. Four future Hall of Famers filled nine of those spots, but none of these guys are members of my all time favorite Buffs starting lineup. “Houston Buffs Forever” is my Buffs club, the one I grew up watching, the one I’d be willling to go to baseball war with as either a field or fantasy all star club manager. These guys were my heroes – and they all played during the years of my “open-to-role-models” years, 1947 to 1953. Anyone who played for the Buffs before or after that time frame had little to no effect upon me as a character mentor, with a few exceptions, but I did continue to learn about life and baseball from all the guys I watched play at Buff Stadium through their last year of 1961. Bob Boyd, who broke the color line in Houston in 1954, would be the biggest example of a teacher who came to me in thr middle of my adolescent years. I admired the cool-under-fire way in which Boyd handled the pressure of performing very well as the first black man to play for the previously all white Houston Buffs. I also loved watching future left fielder Billy Williams, third baseman Ron Santo, and pitcher Mo Drabowsky of the 1960 season club, but none of these guys, not even Boyd, made it to my personal starting lineup – the one I call “Houston Buffs Forever.” Here they are – my personal favorites – now and forever. I’d take on the whole baseball world with these guys – and I’d keep on trying, win or lose, with this same lineup, to excel against all odds. These guys are all a generous blend of baseball character and athletic talent.

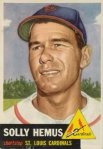

A couple of days ago, I presented y choices for the All Time Buffs team, based upon career performances in the big leagues and their accomplishments with Houston. Four future Hall of Famers filled nine of those spots, but none of these guys are members of my all time favorite Buffs starting lineup. “Houston Buffs Forever” is my Buffs club, the one I grew up watching, the one I’d be willling to go to baseball war with as either a field or fantasy all star club manager. These guys were my heroes – and they all played during the years of my “open-to-role-models” years, 1947 to 1953. Anyone who played for the Buffs before or after that time frame had little to no effect upon me as a character mentor, with a few exceptions, but I did continue to learn about life and baseball from all the guys I watched play at Buff Stadium through their last year of 1961. Bob Boyd, who broke the color line in Houston in 1954, would be the biggest example of a teacher who came to me in thr middle of my adolescent years. I admired the cool-under-fire way in which Boyd handled the pressure of performing very well as the first black man to play for the previously all white Houston Buffs. I also loved watching future left fielder Billy Williams, third baseman Ron Santo, and pitcher Mo Drabowsky of the 1960 season club, but none of these guys, not even Boyd, made it to my personal starting lineup – the one I call “Houston Buffs Forever.” Here they are – my personal favorites – now and forever. I’d take on the whole baseball world with these guys – and I’d keep on trying, win or lose, with this same lineup, to excel against all odds. These guys are all a generous blend of baseball character and athletic talent. SOLLY HEMUS, SECOND BASE: Solly was my first baseball hero back in 1947, that is, unless we don’t count my dad. but he was definitely my first role model from the professional ranks. Hemus played three seasons for the Buffs (1947-49) before going on to his very successful career in the majors with the Cardinals and Phillies. He is still going strong today in the oil business at age 86. Solly went into private business after concluding his tenure in baseball as a manager and coach, but he has stayed in touch with the game and a variety of charitable causes supported by various baseball concerns. Solly Hemus is one of the most humble philanthropists that the game has ever known. He supports a number of worthy works, but he avoids any action that will draw serious attention to his giving. If everyone we know had the heart of a Solly Hemus, and the modesty that only comes from the anonymity of the giver, the world would be a much nicer place for all of us. Solly Hemus is also the only member of the All Time Buffs Performance Club to make my personal Buffs preference team.

SOLLY HEMUS, SECOND BASE: Solly was my first baseball hero back in 1947, that is, unless we don’t count my dad. but he was definitely my first role model from the professional ranks. Hemus played three seasons for the Buffs (1947-49) before going on to his very successful career in the majors with the Cardinals and Phillies. He is still going strong today in the oil business at age 86. Solly went into private business after concluding his tenure in baseball as a manager and coach, but he has stayed in touch with the game and a variety of charitable causes supported by various baseball concerns. Solly Hemus is one of the most humble philanthropists that the game has ever known. He supports a number of worthy works, but he avoids any action that will draw serious attention to his giving. If everyone we know had the heart of a Solly Hemus, and the modesty that only comes from the anonymity of the giver, the world would be a much nicer place for all of us. Solly Hemus is also the only member of the All Time Buffs Performance Club to make my personal Buffs preference team. HAL EPPS, CENTER FIELD: They dubbed him as “The Mayor of Center Field.” His speed and defensive skill spoke to the origins of that nickname, ut he laso patrolled the Buff Stadium middle garden as though there were no term limits on his tenure of service. Long before I ever saw a Buffs game, Hal Epps played in Houston from 1936-1939 and again in 1941-1942. I first saw Hal play during his last three years in Buff Stadium, from 1947-1949. The former Philadelphia A’s and St. Louis Browns outfielder was a pivotal player for the 1947 Houston Buffs’ Texas League and Dixie Series Champions. After he left baseball, Hal Epps lived quetly in the Houston area until his death at age 90 in 2004.

HAL EPPS, CENTER FIELD: They dubbed him as “The Mayor of Center Field.” His speed and defensive skill spoke to the origins of that nickname, ut he laso patrolled the Buff Stadium middle garden as though there were no term limits on his tenure of service. Long before I ever saw a Buffs game, Hal Epps played in Houston from 1936-1939 and again in 1941-1942. I first saw Hal play during his last three years in Buff Stadium, from 1947-1949. The former Philadelphia A’s and St. Louis Browns outfielder was a pivotal player for the 1947 Houston Buffs’ Texas League and Dixie Series Champions. After he left baseball, Hal Epps lived quetly in the Houston area until his death at age 90 in 2004. LARRY MIGGINS, LEFT FIELD: Irish Larry Miggins had a four season stay in Houston (1949, 1951, 1953-1954) as a slugging outfielder for the Buffs. His 28 HR during the 1951 season were a big factor in the Buffs capturing the Texas League pennant that year. He also had a great tenor voice and was sometimes asked to sing at games on special holiday occasions. “When Irish Eyes Are Smiling” is the number I remember best. Miggins was noted for his honesty. One time, when he was playing left field for the Columbus Redbirds in a playoff game, a batter hit a ball over Larry’s head that the umpire ruled a ground rule double for landing in an unplayable area short of the stands. When the other team protested that it was really a home run that had then been dropped into the unplayable area on field, the umpire called time to ask Larry which call was correct. Larry’s words supported the opposing team’s view – that it, indeed, had been a home run for the opposition – thus, costing his own team a run. For that honesty, Miggins was almost run out of the stadium on a rail by the home crowd, but it was honesty the umpire wanted. And honesty is Mr. Miggins’s middle name – or should be. Larry Miggins is one of my dearest friends in the world. Today, at hearly age 84, he still lives in Houston with his lovely Irish wife Kathleen – and very near their surviving eleven grown children and numerous grandchildren.

LARRY MIGGINS, LEFT FIELD: Irish Larry Miggins had a four season stay in Houston (1949, 1951, 1953-1954) as a slugging outfielder for the Buffs. His 28 HR during the 1951 season were a big factor in the Buffs capturing the Texas League pennant that year. He also had a great tenor voice and was sometimes asked to sing at games on special holiday occasions. “When Irish Eyes Are Smiling” is the number I remember best. Miggins was noted for his honesty. One time, when he was playing left field for the Columbus Redbirds in a playoff game, a batter hit a ball over Larry’s head that the umpire ruled a ground rule double for landing in an unplayable area short of the stands. When the other team protested that it was really a home run that had then been dropped into the unplayable area on field, the umpire called time to ask Larry which call was correct. Larry’s words supported the opposing team’s view – that it, indeed, had been a home run for the opposition – thus, costing his own team a run. For that honesty, Miggins was almost run out of the stadium on a rail by the home crowd, but it was honesty the umpire wanted. And honesty is Mr. Miggins’s middle name – or should be. Larry Miggins is one of my dearest friends in the world. Today, at hearly age 84, he still lives in Houston with his lovely Irish wife Kathleen – and very near their surviving eleven grown children and numerous grandchildren. JERRY WITTE, FIRST BASE: My first sacker is one of the greatest sluggers in minor league baseball history. Jerry’s 308 career home runs included the 38 he blasted to lead the 1951 Buffs to a Texas League pennant and, more incredibly for that pre-steroid era, the 50 HR he launched for the 1949 Dallas Eagles. Jerry Witte didn’t simply “”Crawford Box” these homers, he blasted them – high, hard, and faraway into the night or late afternoon skies – and in a manner that reminded of Babe Ruth. They were the baseball trajectory version of the great western Arch Memorial in St. Louis. – As a kid, Jerry Witte was the biggest hero I ever had. As an older adult, he was also my best friend. – A few years ago, I helped Jerry Witte organize and write his memoirs in a fine little book called “A Kid From St. Louis” (2003). (If anyone is interested in a copy, please contact me by e-mail for information about the purchase of a hard-bound first edition. As in all other matters, my e-mail address is houston_buff@hotmail.com . Jerry and Mary Witte were both myclose friends – and they spent most of their lives in the same East End section of Houston where I grew up, and attending the same St. Christopher’s Catchlic School that was my place as a kid. We lost Mary to cancer in 2001. We lost Jerry to a broken heart in 2002 at age 86. Jerry and Mary had seven daughters, whom I love today as if they were my own family. Jerry Witte was the most down-to-earth good man I ever met. Wish we could have kept him forever. The world would be a much better place for it.

JERRY WITTE, FIRST BASE: My first sacker is one of the greatest sluggers in minor league baseball history. Jerry’s 308 career home runs included the 38 he blasted to lead the 1951 Buffs to a Texas League pennant and, more incredibly for that pre-steroid era, the 50 HR he launched for the 1949 Dallas Eagles. Jerry Witte didn’t simply “”Crawford Box” these homers, he blasted them – high, hard, and faraway into the night or late afternoon skies – and in a manner that reminded of Babe Ruth. They were the baseball trajectory version of the great western Arch Memorial in St. Louis. – As a kid, Jerry Witte was the biggest hero I ever had. As an older adult, he was also my best friend. – A few years ago, I helped Jerry Witte organize and write his memoirs in a fine little book called “A Kid From St. Louis” (2003). (If anyone is interested in a copy, please contact me by e-mail for information about the purchase of a hard-bound first edition. As in all other matters, my e-mail address is houston_buff@hotmail.com . Jerry and Mary Witte were both myclose friends – and they spent most of their lives in the same East End section of Houston where I grew up, and attending the same St. Christopher’s Catchlic School that was my place as a kid. We lost Mary to cancer in 2001. We lost Jerry to a broken heart in 2002 at age 86. Jerry and Mary had seven daughters, whom I love today as if they were my own family. Jerry Witte was the most down-to-earth good man I ever met. Wish we could have kept him forever. The world would be a much better place for it. KEN BOYER, THIRD BASE: When Ken Boyer joined the 1954 Buffs, he came with “great major league future” stamped all over his travelling trunk. He could run, hit, throw, hit for average, and hit for power. His 1954 Buffs stats included a .319 batting average, 21 home runs, and 116 runs batted in. He was too good for a second season in Houston, but he was the offensive force of that championship club while he was here. He actually performed better in Houston than Ron Santo did, six years later in 1960. Either guy is a great pick at 3rd base, but I’ll take Boyer as my personal choice – and that’s probably influenced by remnant bias in favor of people and things of the Cardinals over the same from the Cubs. I’m pretty much biased in favor of St. Louis, except for those times they stand in the way of our Houston Astros. Under that circumstance of St. Louis versus my beloved hometown, I’m for Houston all the way. Every time.

KEN BOYER, THIRD BASE: When Ken Boyer joined the 1954 Buffs, he came with “great major league future” stamped all over his travelling trunk. He could run, hit, throw, hit for average, and hit for power. His 1954 Buffs stats included a .319 batting average, 21 home runs, and 116 runs batted in. He was too good for a second season in Houston, but he was the offensive force of that championship club while he was here. He actually performed better in Houston than Ron Santo did, six years later in 1960. Either guy is a great pick at 3rd base, but I’ll take Boyer as my personal choice – and that’s probably influenced by remnant bias in favor of people and things of the Cardinals over the same from the Cubs. I’m pretty much biased in favor of St. Louis, except for those times they stand in the way of our Houston Astros. Under that circumstance of St. Louis versus my beloved hometown, I’m for Houston all the way. Every time. JIM BASSO, RIGHT FIELD: Jim Basso was a Buff in 1946 and for part of the 1947 season. I really didn’t get to know Jim until later in life, but that made up for a lot of lost time. Basso was one of fieriest guys I ever met. His biggest disappointment in life was his failure to reach the big leagues long enough to get into the record books as a former big leaguer. His greatest thrill was meeting and partying with Ernest Hemingway in Cuba during spring training one year in the late ’40s. – If Jim Basso were alive today, I’d want him in my lineup.

JIM BASSO, RIGHT FIELD: Jim Basso was a Buff in 1946 and for part of the 1947 season. I really didn’t get to know Jim until later in life, but that made up for a lot of lost time. Basso was one of fieriest guys I ever met. His biggest disappointment in life was his failure to reach the big leagues long enough to get into the record books as a former big leaguer. His greatest thrill was meeting and partying with Ernest Hemingway in Cuba during spring training one year in the late ’40s. – If Jim Basso were alive today, I’d want him in my lineup. FRANK MANCUSO, CATCHER: I grew up on Japonica Street in Houston’s Pecan Park subdivision in the Est End. Frank Mancuso’s mother lived just down the street on Japonica, at the corner of Japonica and Flowers. My mom knew Frank’s mom. They went grocery shopping together in my mom’s car. Frank Mancuso and his brother Gus were everyday names in my life for as long as I could remember. The former Senator and Brown, who survived a parachute freefall in the Army during World War II – and then got home in time to catch for the only Browns club to ever visit the World Series in 1944 was another great human being. He didn’t reach the Buffs until 1953, but he was already deeply in the heart of Houston as a citizen. After baseball, Frank ran for a place on Houston City Council. He won – and then he stayed there for thirty years as probably the most honest politician to ever serve this community. He represented the East End well and he promoted the improvement of parks and sporting venues for the inner city kids who, otherwise, had little. When Frank left us in August 2007, at age 89, the people of Houston lost a man who really understood what public service was supposed to be about. Frank Mancuso was another good friend that I miss a lot, everyday. No one else could be the catcher of my “Houston Buffs Forever” club.

FRANK MANCUSO, CATCHER: I grew up on Japonica Street in Houston’s Pecan Park subdivision in the Est End. Frank Mancuso’s mother lived just down the street on Japonica, at the corner of Japonica and Flowers. My mom knew Frank’s mom. They went grocery shopping together in my mom’s car. Frank Mancuso and his brother Gus were everyday names in my life for as long as I could remember. The former Senator and Brown, who survived a parachute freefall in the Army during World War II – and then got home in time to catch for the only Browns club to ever visit the World Series in 1944 was another great human being. He didn’t reach the Buffs until 1953, but he was already deeply in the heart of Houston as a citizen. After baseball, Frank ran for a place on Houston City Council. He won – and then he stayed there for thirty years as probably the most honest politician to ever serve this community. He represented the East End well and he promoted the improvement of parks and sporting venues for the inner city kids who, otherwise, had little. When Frank left us in August 2007, at age 89, the people of Houston lost a man who really understood what public service was supposed to be about. Frank Mancuso was another good friend that I miss a lot, everyday. No one else could be the catcher of my “Houston Buffs Forever” club. BILLY COSTA, SHORTSTOP: Little (5’6″) Billy Costa served two stints with the Buffs in 1946-47 and 1951-52. He was another of those Rizzuto-type pepperpot players who kept everyone on their toes, both on and off the field. When Billy came down with polio in 1951, I was crushed by the news. I promptly made all kinds of prayer and pubescent reform deals with God, if He would just cure Billy Costa of his affliction. The efforts of so many kid fans in prayer and bargaining must have done something because Billy Costa was well enough to play for the Buffs again in 1952. After baseball, Billy served a long time in politics as an elected member of the Harris County Commisssioner’s Court. I never met Billy personally, but I always liked him as a player. He died several years ago, long before the normal time span for most people. I’ll take Costa as my “HBF” shortstop, even if he couldn’t hit as well as Phil Rizzuto. Billy never made it to the big leagues.

BILLY COSTA, SHORTSTOP: Little (5’6″) Billy Costa served two stints with the Buffs in 1946-47 and 1951-52. He was another of those Rizzuto-type pepperpot players who kept everyone on their toes, both on and off the field. When Billy came down with polio in 1951, I was crushed by the news. I promptly made all kinds of prayer and pubescent reform deals with God, if He would just cure Billy Costa of his affliction. The efforts of so many kid fans in prayer and bargaining must have done something because Billy Costa was well enough to play for the Buffs again in 1952. After baseball, Billy served a long time in politics as an elected member of the Harris County Commisssioner’s Court. I never met Billy personally, but I always liked him as a player. He died several years ago, long before the normal time span for most people. I’ll take Costa as my “HBF” shortstop, even if he couldn’t hit as well as Phil Rizzuto. Billy never made it to the big leagues. AL PAPAI, PITCHER: On a day when knuckle balls are totally on my mind (I’m attending tonight’s Knuckle Ball Benefit Dinner downtown), Al Papai stands out as the clear choice to be my starting “HBF” pitcher. Al went 21-10 with a 2.45 ERA for the ’47 championship Buffs; he returned to go 23-9 with a 2.44 ERA for the championship ’51 Buffs. When his knuckle ball was bobbing right, nobody could hit it – and few catchers could catch it – but batters still swung at it, hopelessly, in self defense. Papai also had a wry sense of humor. In 1951, he was called upon to escort beauty queen Kathryn Grandstaff to home plate in a pre-game ceremony at Buff Stadium. When that same queen later married crooner Bing Crosby and became something of lesser light movie star, Al Papai enjoyed reminded others of his earlier service to the lady. “Just remember,” Al said, “I gave her the start that made her who she is today!” When Allen Russell was planning the last Round Up of the Houston Buffs in 1995, sadly, Papai’s invitation arrived in Springfield, Illinois on the day of his funeral. Dead at 78, the world lost another of the grandest old Buffs, but he survives here in this roll call of those who played with great heart on the field to take his rightful place with my eight other picks for the “Houston Baseball Forever” nine. As I said earlier, I’d take on the world with these guys playing for Houston in their prime.

AL PAPAI, PITCHER: On a day when knuckle balls are totally on my mind (I’m attending tonight’s Knuckle Ball Benefit Dinner downtown), Al Papai stands out as the clear choice to be my starting “HBF” pitcher. Al went 21-10 with a 2.45 ERA for the ’47 championship Buffs; he returned to go 23-9 with a 2.44 ERA for the championship ’51 Buffs. When his knuckle ball was bobbing right, nobody could hit it – and few catchers could catch it – but batters still swung at it, hopelessly, in self defense. Papai also had a wry sense of humor. In 1951, he was called upon to escort beauty queen Kathryn Grandstaff to home plate in a pre-game ceremony at Buff Stadium. When that same queen later married crooner Bing Crosby and became something of lesser light movie star, Al Papai enjoyed reminded others of his earlier service to the lady. “Just remember,” Al said, “I gave her the start that made her who she is today!” When Allen Russell was planning the last Round Up of the Houston Buffs in 1995, sadly, Papai’s invitation arrived in Springfield, Illinois on the day of his funeral. Dead at 78, the world lost another of the grandest old Buffs, but he survives here in this roll call of those who played with great heart on the field to take his rightful place with my eight other picks for the “Houston Baseball Forever” nine. As I said earlier, I’d take on the world with these guys playing for Houston in their prime.