“Car 8 was built as one of the original 12 cars to inaugurate electric service in June of 1891.” – As with all other photos & text used in these column pictorials, this material is courtesy of Steve Baron, Houston Streetcar History Pages @ http://members.iglou.com/baron/

From its 1836 inception, people saw Houston’s long range potential as a seaport because of its access to the Gulf of Mexico via Buffalo Bayou and Galveston Bay. As the port idea grew in the 19th century, it wasn’t long before incremental improvements to the waterway route over time led to the formal christening of the Houston Ship Channel in 1914. Over this same economic time frame, Houston grew exponentially as a shipping center for cotton, cattle, and that newly found nearby commodity known as oil.

The thing that made it all come together was rail, local and long distance tracks that moved both people and products around town and out of state or country. Had it not been for the invention and growing ecopolitical punch of the spontaneous combustion engine industries, Houston and other developing western cities would have stayed with rail and grown quite differently, but as we know, that is not what happened. A short run at our first local history with rail is still a fun and factually packed trip to take.

“Posed in front of Grand Central Depot (Southern Pacific lines) are brand new “California” car 153, trailer 33, and an 1896-built nine-bench open car. Such was public transit in Houston in 1902. Sic transit gloria mundi!” – Courtesy, Steve Baron, http://members.iglou.com/baron/

Houston’s first mule-drawn streetcars began service in 1868. On May 2, 1874, the Houston City Street Railway began mule-powered operations on Travis Street, marking the true beginning of organized rail service in Houston. By 1889, a competing company, the Bayou City Street Railway began operations. It will later be absorbed by the Houston City Street Railway.

On June 12, 1891, the first local operation of electric streetcars began. In 1892, the Houston Heights line also opened. For several years thereafter, it operated as a separate company.

In 1896, a court-ordered receivership forced the sale of the Houston City Street Railway. It was reorganized by its new owners as the Houston Electric Street Railway. In 1901, following another receivership, the street railway was sold to investors associated with the Stone & Webster firm of Boston, Mass. It was reorganized this time as the Houston Electric Company.

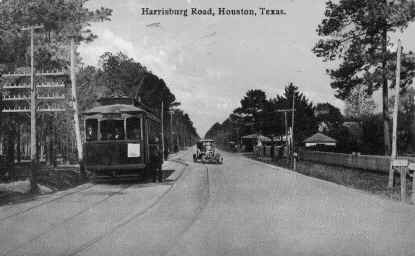

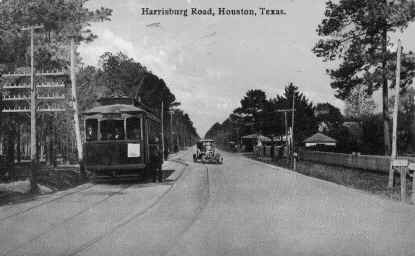

“The Harrisburg line was opened to streetcar traffic in 1908, and this postcard view was made not long after. The car is a double-truck semiconvertible design, the mainstay of the fleet during this period.” – Courtesy, Steve Baron, http://members.iglou.com/baron/

By 1908, the Harrisburg line opened from downtown to Houston’s growing east end. By 1910, the Bellaire line opened to the west from South Main along the lazy country lane that is now the car-clogged boulevard we know as the Holcombe-Bellaire continuum. My mom spoke often of how she and my maternal grandparents took the street car south from their home in the Heights back in the 1920s to visit relatives in Bellaire. “By the time we transferred way out South Main to the Bellaire line,” Mom said, “it already felt like we were way out in the country. Now we’re getting ready for a rail ride through the woods. There wasn’t anything out there back in the 1920s. Then, when, you finally got to Bellaire, there wasn’t much there either, except for relatives and a few strange folks that we didn’t know.”

On December 5, 1911, the Interurban route to Galveston opened. The Galveston-Houston Electric Railway operated as a separate company from HECo., but it too remained under the ownership and control of the parent company. By 1911, public service companies were sensitive to the need for obscuring any kind of expansion that might begin to look to federal authorities like a monopoly. That ball would stay in economic play forevermore, except for periods of obvious disregard.

“A busy downtown scene in the late 1920’s finds car 416 on the Mandell line, preparing to head outbound to the Montrose district. These cars, built in 1927, were the last series of streetcars ordered by the Houston Electric Co. (There were two later experimental cars, but that’s another story.)” Courtesy, Steve Baron, http://members.iglou.com/baron/

The downtown shot of this Mandell Line car also features the newer kid on the block in the far ight hand corner. The automobile was making its presence felt big time in Houston as the city rolled through the Jazz Age on its way with the rest of the country to the Great Depression.

The appeal of cars always was the fact that they weren’t tied to fixed route travel by tracks. Their growing affordability and the bountifulness of cheap gas made them a growing-in-popularity alternative to rail travel. Since 194, some individual attempted to use their cars as public transport “jitney” service upon open and fixed routes. These were finally banned by City Council in the early 1920s in favor of public busses. On April 1, 1924, the first Houston bus route, on Austin Street, began operations in Houston in the wake of a city referendum outlawing jitneys.

The 1930s saw the growth of bus service and private automobile use. By the end of the decade, the streetcar and interurban rail lines were dead. On October 31, 1936, the last run of the Galveston-Houston interurban line clattered its way north and south between the two cities. The section that served people from downtown to Park Place, however, continued under HECo. operation until 1940.

On June 9, 1940, the Houston Electric Company took its last run with electric rail streetcars. The final two routes to give way to automobiles and busses were the lines serving Pierce and Park Place. Even by this time, local highly placed politicians and real estate entrepreneurs were beginning to plan freeways that would both “solve” the growing congestion problem of increasing auto travel and more privately and quietly help certain individuals invest and profit from planned growth to the far-reaching suburbs that they also would create from the recent earlier purchase of cheap land on the nearby prairies woodlands.

“A 1930’s view of one of Houston’s single-truck Birney cars. Built in 1918, this was one of several cars that were modernized in the company shops, changing them from double-end to single-ended, and installing full length doors with inside steps.” – Courtesy, Steve Baron, website: (http://members.iglou.com/baron/)

Once again, in 2010, the inner, older, and more compact center of Houston is being best served practically by new rail service. The far-reaching Houston, the one that grew from the ambitions of the few and the addiction of us all to the automobile, is now unserviceable by any single form of mass public transportation – nor are we inclined in Houston to want to use public transportation as anything other than an occasionally quaint reminder of our long ago past.

It is what is. And we are what we are. Take me out to the ballgame, but let’s use your car or mine.

For a complete look at the magnificent work that historian Steve Baron has done on the history of rail transportation in Houston, please do yourself a favor and check out his website, Houston Streetcar History, at http://members.iglou.com/baron/