Over the years of their total existence in the 20th century as the Houston Buffaloes, or Buffs, our minor league baseball club produced some pretty fine baseball players, Tris Speaker and Dizzy Dean, most notably. come to mind. In 1920, Mr. Speaker also went on to become the first former Buff to win a World Series as a major league manage . He was followed by four other ex-Buff players who managed at least one big league club to a World Series crown. This total list of five former Buff World Series Winning Managers includes Tris Speaker, Eddie Dyer, Danny Murtaugh, Walt Alston and Johnny Keane – a quietly spoken testimony to Houston as baseball’s version of football’s “Cradle of Coaches,” or, more accurately in this case, a baseball “Cradle of Managers.”

Numerous other former Buffs, including men like Solly Hemus, have also done some quality time as big league field generals, but probably no year ever equalled what happened in the tough off-production year of 1937. That was the season that two future World Series winning managers and another pretty good one stumbled through a low finishing time as players for the low-performing 1937 Buffs.

John Watkins also returns to The Pecan Park Eagle as a guest columnist this morning to bring us that story. – Bill McCurdy:

Three Great Future Managers from the 1937 Houston Buffs

By John Watkins, Guest Columnist jnowat@gmail.com

The 1937 season was not a memorable one for the Houston Buffs, who finished seventh in the Texas League with a 67-91 record, 33.5 game behind first-place Oklahoma City. Attendance dropped along with the Buffs’ winning percentage, avraging fewer than 1,000 fans per home game. One highlight of the dreary season was the league’s second all star game, played July 17 at Buff Stadium before a crows of more than 8.000.

The fans also caught a glimpse of three Houston players who would become major league managers: Johnny Keane (Cardinals, 1961-1964; Yankees, 1965-1966), Walter Alston (Dodgers, 1954-1976), and Herman Franks (Giants, 1965-1968; Cubs, 1977-1979).

Johnny Keane was in his third season with the Buffs in 1937. At age 25, he was a veteran ballplayer with seven professional seasons under his belt. In 1935 and 1936, he was the Buffs’ regular shortstop, but in 1937 he played primarily at third base and hit .267 in 158 games. Thereafter, the Cardinals made him a player-manager in their organization, and that proved to be his path to the major leagues, where he was a coach and manager. The 1935 season was pivotal in this change in direction. That year, Keane was hit by a pitch and suffered a skull fracture that left him near death for two weeks.

After managing in the low minors, Keane returned to the Buffs in 1946 for what became a three-year stint as manager. In 1947, the team finished first with a 96-58 record, nosing out the Fort Worth Cats by a half-game. While the Buffs swept Tulsa in the first round of playoffs, however, the Cats lost to Dallas in seven games. Houston then dispatched Dallas, four games to two, to win the championship and went on to defeat Mobile in the Dixie Series. Keane moved up to Rochester, the Cardinals’ farm team in the Class AAA International League in 1949 and led the Red Wings to a first-place finish the next season. After another year in Rochester, he served seven seasons in the Triple A American Association before joining the Cardinals in 1959 as a coach under manager Solly Hemus, his second baseman on the 1947 Buffs.

When the Cardinals dismissed Hemus in July 1961, Keane was given the top job. In the tumultuous 1964 season, his Redbirds overtook the faltering Philadelphia Phillies to win the pennant by one game and then defeated the New York Yankees in the World Series. St. Louis owner Gussie Busch had fired general manager Bing Devine when it appeared that the Cardinals had no chance to catch the Phillies, and at that time he was reportedly planning to fire Keane at the end of the season. After the World Series, however, Busch was prepared to offer Keane a multi-year contract. In a stunning development, Keane resigned to take over the Yankees from Yogi Berra, who had just lost his job.

In New York, Keane inherited a team in decline. With several players benched by injuries in 1965, the Yankees fell to sixth place with a 77-85 record. The next season was worse. Through the first ten 10 games, New York’s record stood at 1-9; through 20, it was 4-16. At that point, the Yankees fired Keane and replaced him with Ralph Houk. The team was then last in the American League, and that is where it finished the season. On January 6, 1967, Keane died of a heart attack at age 55 in Houston, where he had made his home since 1935. He is buried at Memorial Oaks Cemetery.

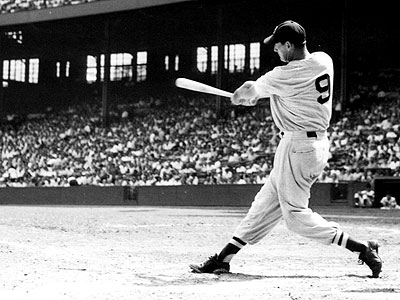

Walter Alston was 25 years old in 1937 but only in his third year as a professional player, having graduated from Miami University in his native Ohio before joining the St. Louis “chain gang.” A first baseman, he split the season almost equally between Houston and Rochester, the Cardinals’ Class AA farm club in the International League. For the Buffs, Alston hit only .212 in 65 games. He fared better in Rochester, batting .246 in 66 games.

The year before, he was called up to St. Louis at the end of the 1936 season and got into the final game, against the Cubs at Sportsman’s Park. It turned out to be his only appearance in the major leagues, and it came about when Cardinals first baseman Johnny Mize was ejected arguing with the umpire over a called strike. Alston made one error in two chances and struck out in his sole at-bat.

The Cardinals made Alston a player-manager in 1940 when he took over their farm team in the Class C Middle Atlantic League. He was there for three seasons and then had back to Triple A as a player for Rochester in 1943, but the Cardinals released him before the season ended. By that time, former St. Louis executive Branch Rickey had moved to the Dodgers, and he hired Alston as a minor-league manager. Starting in the Class B Interstate League in 1944, Alston steadily moved up in the Dodgers’ organization, reaching Triple A Montreal of the International League in 1950.

After four seasons in Montreal, Alston took over the Brooklyn club in 1954. He managed the Dodgers for 23 years, leading them to four World Series titles (the first in Brooklyn in 1955, the others in Los Angeles) and seven National League pennants. He was known for his studious approach to the game and for signing only one-year contracts with the Dodgers even as multi-year contracts became common. His 2,040 wins as a manager rank ninth on the all-time list. He was inducted into the Hall of Fame in 1983 and died at age 72 on October 1, 1984, in Oxford, Ohio.

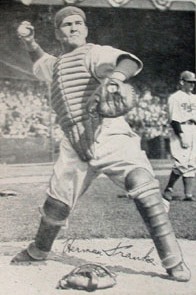

Herman Franks appeared in only 10 games for the Buffs in 1937 and hit just .130 in 23 at-bats. A 23-year-old catcher, he had begun his pro career five years earlier. Franks spent most of the 1937 season at Sacramento, the St. Louis affiliate in the Class AA Pacific Coast League, where he hit .265. He eventually made it to the Cardinals for 17 games and 21 plate appearances in 1939, but the club sold his contract to Brooklyn in early 1940. Franks was the Dodgers backup catcher in 1940 and 1941 under manager Leo Durocher, who became a mentor. After Franks was discharged from the Navy after World War II, he played alongside Jackie Robinson on the Dodgers’ Montreal farm team that won the 1946 International League pennant.

In 1947, Branch Rickey named Franks as player-manager of the St. Paul Saints, the Dodgers’ Double A affiliate in the American Association. In August, however, Connie Mack told Rickey that the A’s needed a backup catcher, and Franks was sent to Philadelphia. He also played for the A’s in 1948. The next season, Durocher, by then the Giants’ manager, hired Franks as bullpen coach. Franks also made his final appearance as a player that season, going 2-for-3 in one game.

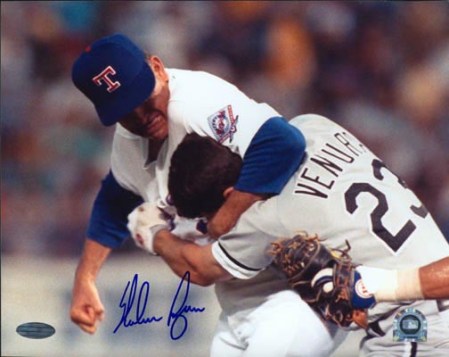

According to Joshua Prager’s book, The Echoing Green (Pantheon 2006), Franks played a crucial role in Bobby Thomson’s “Shot Heard Round The World,” the home run off Brooklyn’s Ralph Branca in the 1951 National League playoffs that won the pennant for the Giants. On Durocher’s orders, Prager says, Franks was stationed in the team’s center-field clubhouse at the Polo Grounds, where he used a telescope to steal the Brooklyn catcher’s signs and relay them to the Giants’ coaches and hitters.

As a manager, Franks had very good teams in San Francisco but finished second four consecutive seasons despite winning more than 90 games three times. (In 1965 and 1966, the arch-rival Dodgers won the National League, and in 1967 and 1968, the Cardinals captured the pennant.) Franks was not as successful in his three years with the Cubs, who finished no higher than third and never won more than 81 games. Franks died at age 95 on March 30, 2009, in Salt Lake City.