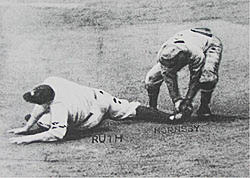

Who were these guys? The seated fellow on the far right end seems to be wearing a light cap with the letter "B" in the crown. Could the "B" easily stand for Brownwood, the Texas town where the photo was finished?

According to this marking on its back, this photo was this photo was finished by Taylor Brothers in Brownwood, Tex

This photo is a gift that arrived yesterday from my friend Sumner Hunnewell of Arnold Missouri in the St. Louis area.Sumner knows that I love anything pictorial on the early days of baseball, especially if it has anything to do with early baseball teams in the State of Texas.

We don’t know anything about the photo beyond what’s written on the back that it was “finished” by Taylor Brothers of Brownwood, Texas and that one of the players (front row, far right) appears to be wearing a lighter-colored cap with a “B” on the front crown quadrant. “Brownwood appears to be the obvious locale of the team, but this was real cowboy country back in the day, and still is. The “B” could have stood for the team’s nickname, Something like “Broncos” or “Bulls” would have worked fine, except that most town teams preferred to identify most closely with their places of origin.

A fellow named Ted Kapnick gave the photo to Sumner Hunnewell. Kapnick owned a college wood bat club known as the Farmington Browns of the KIT collegiate summer league program last year. Kapnick had also received the photo as a gift from yet another friend in New Jersey. I’ve also now heard from Ted Kapnick and he has promised to see what the NJ friend knows about the photo too. Who knows? This may be a mystery that’s been passing from hand to hand for something close to a century of time now, but that’s OK. The added mystery simply amplifies the photo’s “orphan in the storm of baseball history” status with me. As for me, the bond with this picture hit instantly. The photo now has a permanent home will give it the best perpetual care I am able to provide – and I also will do what I am able to establish and confirm its identity with the your help of all you out there who also care about and misplaced artifacts.

Is there anyone out there who is familiar with the Brownwood, Texas area? I plan to contact their library and local schools, but any special information you may have too could be very useful here. Feel free to contact me through the comment feature on this article or simply drop me an e-mail message at houston_buff@hotmail.com .

Now that I’ve set forth the straightforward research question at hand, here’s what I came with as my fictional account of who each of these twelve Texas cowboy types are by name, age, position, and local employment as members of the “Brownwood Broncos” (also fictional). As I said earlier to Sumner Hunnewell, these guys look tough enough to have played a triple header on Sunday and then headed out at Monday dawn on a one thousand head of cattle drive from Brownwood, Texas to Dodge City, Kansas. (Sunday blue laws prohibiting the sale of alcohol or the playing of baseball or the general pursuit of pleasure on the Sabbath did not rule all Texas communities.) Naturally, I could only get there by way of a minor digression into lyrical verse.

The Brownwood Broncos: A Fictional Account of the Players in the Photo:

Brownwood

Boys of Brownwood,

Eased away for the day,

From the cattle ranges,

Downtown grain stores and pool halls,

From Sam’s Barber Shop and Jeb Hooker’s Saloon.

Today they each ride a different horse,

Today they mount the diamond range,

Today they are the twelve men of game-heart,

Today they play ball as the Brownwood Broncos.

In fantasy, they ride as follows,

From left to right, back row first:

Back Row, Left to Right ~

Clinton Farley, 24, CF-SS, cowboy, Johnson Ranch;

Shorty Mazar, 29, 2B-LF, barber, Sam’s Barber Shop;

Tillman Stoker, 32, 1B, range foreman, Johnson Ranch;

Harvey Kellogg, 48. Manager-P, Mayor, Brownwood, Texas;

Bitsy Cole, 27, SS-CF, Western Union Telegrapher, Brownwood;

Henry Veselka, 38, OF-P, Smejkal’s Seed & Feed, Brownwood;

Front Row, Left to Right ~

Corky Collins, 31, RF-P, chuck wagon cook, Johnson Ranch;

Billy Bob Johnson, 22, C-3B, rancher’s son, Johnson Ranch;

Theo Hydecker, 26, LF-2B, blacksmith, Brownwood;

Oscar Gruber, 27, 3B-C, clerk, Wells Fargo Bank, Brownwood;

Ashley Taylor, 26, P-1B, photographer, Taylor Bros, Brownwood;

Albert Taylor, 26. P-OF, photographer, Taylor Bros, Brownwood.

Bottom Line: Now let’s find out who these guys really were.