I first wrote this basic article over on the Houston ChronCom site back on July 11, 2008. Due to renewed interest that fired from the spark of yesterday’s Jim Menutis article, here it is again. The City Auditorium was the site of some memorable concerts and appearances by some iconic people. Certainly the famous stand of Fats Domino there against segregation was major – as was the early 1930s appearance by Babe Ruth for a role model talk to the youth of Houston, but even these major events failed to leave the old place with its major venue identity.

You see, the City Auditorium will always be first remembered as the home of Friday Night Wrestling. Let’s have a nice familiar-face look this morning at that little file in Houston History:

City Auditorium ~ Houston, Texas

The City Auditorium in Houston, located at 615 Louisiana, thrived from 1910 until 1962 as the downtown site of some top of the line historical speakers and entertainers. As mentioned earlier, Babe Ruth spoke there during the early 1930s. Elvis Presley performed there in 1955. Countless religious figures, including Billy Graham, conducted revivals there over the years.

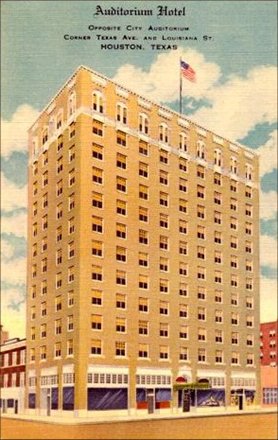

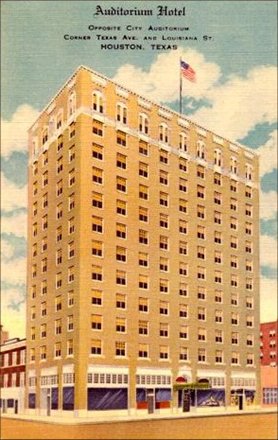

The above photo is facing north. The tall building at the top is where most guests stayed, if they played the City Auditorium. It’s the Lancaster Hotel now. It was called the City Auditorium Hotel back then.

The Lancaster – in its days as The City Auditorium Hotel

The Lancaster Hotel is now the commodious and convenient place to be for those happy out-of-towners attending symphony concerts at the City Auditorium’s successor, Jones Hall, the venue that replaced the old auditorium in 1966.

For as long as we are honestly trying to maintain the true history of what has gone on in Houston over the years, we shall never be able to dismiss the most popular act that ever played this site as the very heart of the old City Auditorium’s dance card. The post World II popularity of professional wrestling married with the advent of television to make “Friday Night TV Wrestling” the most popular show in Houston for years.

Wrestling was not new to Houston after World War II. It had been around since the 1920s under the promotional drive of the late Morris Siegel. Wrestling just took to the “Big Eye” like fried eggs to a hot skillet. The combination instantly and simply cooked up the answer to every Houstonian’s hunger for easy answers to the many questions of Good versus Evil.

You didn’t have to think. All you had to do was watch.

We all knew it was fake. (OK, maybe 80% of us knew it was fake.) But it still didn’t matter. We tuned in to see the Good Guys and Good Gals win. (Yep!. We had “lady wrestlers” in those days too.) It would be impossible to recount them all here, but I will try to cover my favorites with a few words of special remembrance.

First of all, everything about Houston wrestling begins and ends with the name of one man, a man named Paul Boesch.

Paul Boesch followed Morris Sigel as Houston’s iconic wrestling promoter.

Paul Boesch (shown above) was a mostly retired wrestler with caulifower ears and a sharp, articulate intelligence. Boeach had an incredible intuitive feel for the dramatic moment and how to use the grudge element as everyday fodder for TV melodrama. As the announcer, and later as the promoter who replaced Morris Siegel, Paul Boesch was a master genius at knowing how to give the public what they wanted.

Once, in 1951, a bad guy wrestler named Danny Savich came on Boesch’s show to explain his atrocious behavior in a match he had just “won.” Instead of explaining, he punched out Paul Boesch too, daring him to do anything about it. By show’s end, Boesch had recovered enough to tell us over the air that he had spoken with Mr Siegel by phone – and that he would be making a one-match comeback next Friday to answer Danny Savich’s challenge.

There was just one catch. Because Paul Boesch was wrestling on the next card, he could not also broadcast that next Friday too. Anyone wanting to see the Boesch-Savich main event would have to buy tickets and see it live. I didn’t get to go, but I couldn’t wait to see the Saturday morning Houston Post sports page report. To my smiling great pleasure, the headline read: “BOESCH KOs SAVICH!”

Irish Danny McShane drew love and hate.

I hated Danny Savich, but I loved Irish Danny McShane! “Irish Danny” was sort of a gray-colored anti-heroic fellow in this black and white world, one who could be a good guy or a bad guy, depending upon the character of the other wrestler and the circumstances of how right and wrong was tilting in the wind on a particular Friday. In other words, McShane was sort of a politician who wrestled. He could stand up for justice, if that’s what the fans seemed to want. Or, if need be, he could remove a bar of soap he had hidden in his wrestling trunks and rub it in a opponent’s eyes, if that would help him win. On those times he battered a foe down or unconscious, McShane had this little bold chesty rooster strut he did around the ring. It angered the fans who didn’t like him, and it frequently had a way of reviving the fallen opponent, who then would suddenly get up and whip Danny’s donkey until he begged for mercy! I hated it when I saw Danny beg. “Get up and fight, you big galoot,” I would yell at the tiny TV screen, but, if it wasn’t in the script that night, poor Danny would just get whipped. Then I got to hate him too for giving up – at least, for a while.

Duke Keomuka – He karate chopped his foes before they even called those open hand blows to the neck by that term.

In the Post World War II era, Hawaiian-born Duke Keomuka was cast in the role of a guy who was still fighting the Battle of Iwo Jima – on the side of the Japanese! Buried deep in that politically incorrect era were all kinds of racial hatreds that I couldn’t stand, even then. “How can you take sides with that dirty Jap?” some of the other kids would ask me. “That’s easy,” I answered. “The guy is really an American too. He’s just a great performer and he does things that nobody else can do! Besides, the war is over. My uncle fought there. And even he doesn’t hate all the Japanese people as you seem to hate them!” (I wasn’t the most articulate opponent of blind racial hatred in those days, but I tried.)

What could Keomuka do? He was the only wrestler back then who took his foes down with karate chops, and he was also the guy who taught all the others how to win a match with the “Asian sleep hold,” a move that fell only inches and seconds short of outright strangulation.

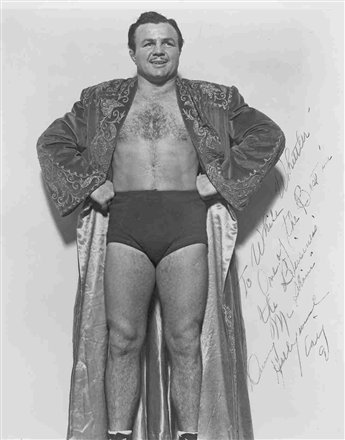

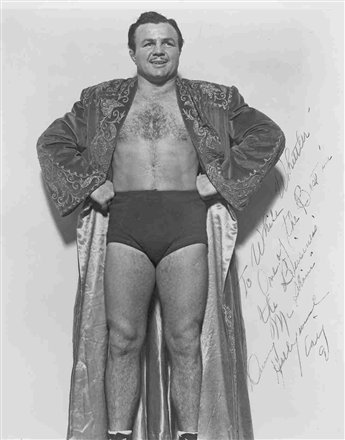

Boston’s Wild Bull Curry was a non-stop, two-fisted fury. The former boxer turned grappler never saw a chin he didn’t like to smack until its owner fell unconscious.

Wild Bull Curry had no redeeming or likable social qualities. He was just mean, mean, mean – and totally inarticulate on the verbal level. All he seemed to want was to separate every competitive head he saw from the shoulders of its owner, bashing his way mindlessly as a mad dog, I guess, to the top of the wrestling world. As far as I know, he never made it, but he sure left a large number of other wrestlers with smashed faces and heavy headaches along the way.

Miguel “Black” Guzman

Miguel “Black” Guzman was a highly popular Good Guy and a very big star with Hispanic wrestling fans. Guzman later became one of my favorite customers when I was selling mens clothes at Merchants Wholesale Exchange as a working UH college student. Blackie always came into the store with this beautiful woman. I never asked about their relationship. I was afraid to ask. Besides, it was none of my business. – Whatever happened in Merchants Wholesale – stayed in Merchants Wholesale!

Rito Romero. You always knew that Rito was a Good Guy. It took the PA announcer twenty seconds to say his name prior to bouts.

Rito Romero was another popular Hispanic Good Guy wrestler. When he and Black Guzman fought as a tag team against Duke Keomuka and Dirty Don Evans, some of the TV viewers trucked downtown and spilled into the live attendance crowd.

Dirty Don Evans Went to Our Church (I think).

Dirty Don Evans held nothing back. He specialized in rubbing soap into the eyes of his opponents to make sure that they could see cleanly, if not clearly, I suppose. As dirty as he did it at work, Evans also attended our church on Sundays during his stays in Houston. At least, I always thought this one guy was Evans. He sure looked like him, but maybe I was wrong. Not once did I ever see the guy in church rub soap in the eyes of the person sitting in the pew ahead of him. So, maybe it wasn’t Dirty Don after all.

Ray Gunkel, Getting Advice from Jack Dempsey

Ray Gunkel was the ultimate pretty boy Good Guy when he started his career in his 20s. When he returned to Houston in his 40s, he had transformed into one of the most mean-spirited Bad Guys in town. Must’ve been something he ate, maybe something like … alimony payments? I can’t think of anything else that may have turned a good man into somebody that mean over a fairly short passage of time.

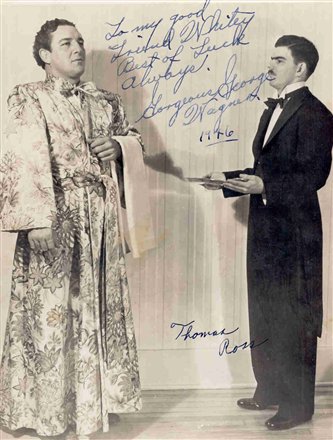

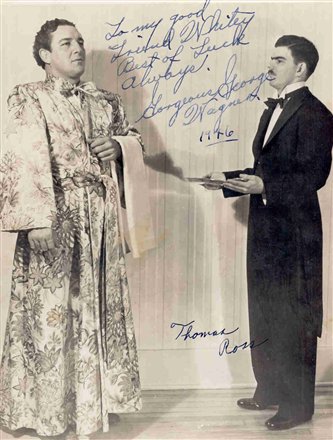

Gorgeous George dropped out of Milby High School in Houston.

Gorgeous George Wagner was a drop out from Milby High School in the Houston East End who went on to become the most famous wrestler of the early TV era. He sprayed the ring with perfume, dispensed golden bobby pins, and strutted around the ring like a haughty woman on his way to committing some dirty mayhem of his own upon “unsuspecting” opponents.

Those were the days, my friend. If you could suspend your recognition of the bogus reality that was pro wrestling back in the day, it was a great Friday night escape for Houstonians of a half century ago. And it was too, without a doubt, the main reason that most people remember the old City Auditorium today.

The place lived for years as the home of professional wrestling in Houston.

Try not to grunt and groan too much today, folks. It’s Friday and the weekend is upon us. Unfortunately for all of us, including those of you who are too young to remember: There is no more City Auditorium. No Jimmy Menutis. No Tin Hall. And, maybe worst of all, no Valian’s.

Have a nice weekend, anyway.

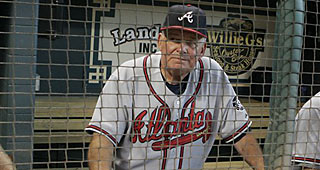

The Astros honored Bobby Cox prior to Tuesday night’s game and well they should have. Good for the Astros! And good for Bobby Cox! What a worthy and often frustrating opponent he was to our Houston aspirations over the years. Will we ever forget the eighteen inning marathon victory over the Braves in the 2005 playoff game at Minute Maid Park? More painfully, will we ever be allowed to dis-remember that play at the plate in the Dome in 1999 that allowed the Braves to knock us out of the playoffs because Cox’s drawn in infield with the bases loaded did what they had to do, via a 6-2 Walt Weiss miraculous force out stop and throw, to kill our playoff chances?

The Astros honored Bobby Cox prior to Tuesday night’s game and well they should have. Good for the Astros! And good for Bobby Cox! What a worthy and often frustrating opponent he was to our Houston aspirations over the years. Will we ever forget the eighteen inning marathon victory over the Braves in the 2005 playoff game at Minute Maid Park? More painfully, will we ever be allowed to dis-remember that play at the plate in the Dome in 1999 that allowed the Braves to knock us out of the playoffs because Cox’s drawn in infield with the bases loaded did what they had to do, via a 6-2 Walt Weiss miraculous force out stop and throw, to kill our playoff chances?