When Cecil Cooper was named manager of the Houston Astros in late 2007, the fact that he’s black was not covered by the current media as even an interesting footnote to the fact that it then had been a little more than fifty-three years since Houston saw it’s first black baseball player take the field to play for a racially integrated Houston sports team. – Think about it. From the time Houston “welcomed” it’s first black baseball player to the time it saw its first black manager in baseball, fifty-three years and three months had passed.

When Cecil Cooper was named manager of the Houston Astros in late 2007, the fact that he’s black was not covered by the current media as even an interesting footnote to the fact that it then had been a little more than fifty-three years since Houston saw it’s first black baseball player take the field to play for a racially integrated Houston sports team. – Think about it. From the time Houston “welcomed” it’s first black baseball player to the time it saw its first black manager in baseball, fifty-three years and three months had passed.

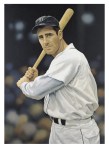

Thursday, May 27, 1954 shall forever remain a special date in my personal memories of the Houston Buffs. That was the date that Bob “The Rope” Boyd made his debut as a first baseman for the Houston Buffs in old Buff Stadium. (They called it Busch Stadium by then, but I stood among those who never bought into the name change when August Busch bought the St. Louis Cardinals and all their organizational holdings, including the Houston Buffs and the ballpark, a year earlier in 1953.)

Buffs General Manager Art Routzong had purchased the contract of Boyd from the Chicago White Sox about a week earlier than his debut in an effort to help the club make their eventually successful run at the 1954 Texas League championship. That was quite a club, one that also featured a rising future Cardinal star at third base named Ken Boyer.

Bob Boyd would prove to be the hitting and defensive specialist that the club needed to anchor the right side of the Buffs infield as strongly as young Boyer held down the left side. Boyd hit .321 for the ’54 season and he followed that production with the ’55 Buffs by posting a .309 mark.

It all started on a night of great change in the face of Houston sports.

I was drawn to the ballpark that 1954 twilight eve as a 16-year old kid who wanted to see Bob Boyd break the color line and, hopefully, have a good first night for the Houston Buffs. The fact that I had just started to drive by that time and needed a good excuse to borrow the family car also factored into the equation. When I borrowed the car, I told my dad why I needed to be there at the ballpark that night. I wanted to see Bob Boyd play for the Buffs as the man who broke the color line in Houston.

fact that I had just started to drive by that time and needed a good excuse to borrow the family car also factored into the equation. When I borrowed the car, I told my dad why I needed to be there at the ballpark that night. I wanted to see Bob Boyd play for the Buffs as the man who broke the color line in Houston.

Although I had grown up in segregated Houston, I was blessed with parents who taught love and acceptance over hate, even though they also had been raised with that blind acceptance of segregation as the way of life. Whatever it was, my parents held beliefs that left the door open for me to actively question the unfairness of segregation and to also embrace Jackie Robinson as a hero when he broke the big league color line in 1947.

No one in the family or the neighborhood wanted to go with me that night, so I went alone. I also bought a good ticket on the first base side with a little money I had earned that week from my after-school job at the A&P grocery store. I also had to buy a dollar’s worth of gas as my rental on the use of dad’s car.

There were only about 5,000 fans at the game that night and almost half of them were the blacks who were then still forced to sit separately in the “colored section” bleachers down the right field line.

The atmosphere was contrasting and electric. The so-called “colored section” fans were rocking from the earliest moment that Bob Boyd first appeared on the field in his glaringly white and clean home Houston Buffs uniform to take infield with the club. While we felt the rumble of all the foot stomping that was going on in the “colored section,” only a few of us white fans stood to show our support with the understated and reserved applause that we white people always do best at times when more raw-boned enthusiasm would have been better.

“Enthusiasm” evened into a loud foot-stomping roar from all parts of Buff Stadium when Bob Boyd finally came to bat in the second inning for his first trip to the plate as a Houston Buff and promptly laced a rope-lined triple off the right field wall. Even those whites who had been sitting on their wary haunches prior to the game rose to cheer for Bob Boyd and his first contributions to a Buffs victory, and, whether they realized it or not, to cheer for another hole in the overt face of segregation in Houston.

Here’s a taste of how iconic sports writer Clark Nealon covered it the next morning in the Houston Post:

“Bob Boyd Sparkles in Debut As Buffs Wallop Sports, 11-4”

by Clark Nealon, Post Sports Editor

“Bob Boyd, the first Negro in the history of the Houston club, made an impressive debut Thursday night.

“The former Chicago White Sox player banged a triple and a double and drove home two runs as the Buffs pounded the Shreveport Sports, 11-4, and Willard Schmidt recorded his sixth victory without a defeat.

“Before one of the largest gatherings of the year – 5.006 paid including 2,297 Negroes – the Buffs started like they were going to fall flat on their faces again, got back in the ball game on bases on balls, then sprinted away with some solid hitting that featured Dick Rand, Kenny Boyer, and Boyd.

“Rand singled home the two go ahead runs in the first, added another later. Boyer tripled with the bases load for three runs batted in and Boyd tripled in a run in the second and doubled in another to start a five-run outburst in the fourth that settled the issue. …

” … Boyd was the center of attention Thursday night, got the wild acclaim of Negro fans, and the plaudits of all for his two safeties and blazing speed on the bases.”

Yes Sir! Yes Maam! May 27, 1954 was a big day in Houston baseball, Houston sports in general, and a moment of positive change in local cultural history. So was Tuesday, August 28, 2007, the day that Cecil Cooper made his debut as a manager for the Houston Astros, a day for change, but it had nothing to do with race. Cecil just didn’t get here quite as loudly and, for reasons that have nothing to do with race, he also may leave soon, just as quietly, but maybe not. Maybe the Astros won’t unload all of the 2009 Astros’ failures on the back of their skipper.

2007, the day that Cecil Cooper made his debut as a manager for the Houston Astros, a day for change, but it had nothing to do with race. Cecil just didn’t get here quite as loudly and, for reasons that have nothing to do with race, he also may leave soon, just as quietly, but maybe not. Maybe the Astros won’t unload all of the 2009 Astros’ failures on the back of their skipper.

In Houston baseball and general sports history, there was only one Bob Boyd. By the time professional football and basketball arrived here, integration was already a part of the total team package. The job of proving that race should not be a factor never had to ride again on the back of one individual player. Bob Boyd already had unlocked, opened, and oiled that gate for all who have come after him – and he did it all back in 1954.

After the 1955 Buffs season, Boyd’s performance at AA Houston earned him a second shot at the big leagues with the Baltimore Orioles. Bob had made a promising start with the Chicago White Sox (1951, 1953-54), but now. after Houston, the now 29-year old lefthanded first bagger seemed primed for a really fine major league career.

In 1956, it was time for Bob Boyd to shine in the big leagues, indeed!

Bob Boyd roped off full season batting averages of .311, .318, and .309 in his first three Oriole seasons (1956-58). His 1959 full season average dropped to .265, but he bounced back in 1960 to hit .317 in 71 games for Baltimore. Boyd played one more limited time season in 1961 for Kansas City and Milwaukee, completing his 693-game big league career with a total batting average of .293 with 19 home runs over nine seasons. Bob Boyd played three more seasons in the minors after 1961 (1962-64) and then retired completely as an active player. Interestingly too, most of Boyd’s last three years were spent in the minor league farm system of the then baby new National League Houston Colt .45s at San Antonio and Oklahoma City.

Following his far better than average baseball career, Bob Boyd returned to his home in Wichita, Kansas, where he worked without complaint as a bus driver until he reached retirement age. Bob died in Wichita at age 84 on September 27, 2004. Today, the man who started his career with the Memphis Red Sox (1947-49) of the Negro Leagues is honored as a member of the Negro League Hall of Fame and also the National Baseball Congress Hall of Fame. Hopefully, we shall always continue to remember and honor Bob Boyd and all others who took the first step toward changing things that needed to change. Bob Boyd did his job with grace, dignity, and tremendously unignorable ability.

Following his far better than average baseball career, Bob Boyd returned to his home in Wichita, Kansas, where he worked without complaint as a bus driver until he reached retirement age. Bob died in Wichita at age 84 on September 27, 2004. Today, the man who started his career with the Memphis Red Sox (1947-49) of the Negro Leagues is honored as a member of the Negro League Hall of Fame and also the National Baseball Congress Hall of Fame. Hopefully, we shall always continue to remember and honor Bob Boyd and all others who took the first step toward changing things that needed to change. Bob Boyd did his job with grace, dignity, and tremendously unignorable ability.

Dead center field in Buff Stadium was 424 feet from home plate. and the outfield pasture also included a free-standing flagpole of some considerable similarity to the one that now resides in Minute Maid Park. It was located about five feet in from the outer wall, but there was no hill to climb.

Dead center field in Buff Stadium was 424 feet from home plate. and the outfield pasture also included a free-standing flagpole of some considerable similarity to the one that now resides in Minute Maid Park. It was located about five feet in from the outer wall, but there was no hill to climb.

Aaron Pointer (Batted Right/Threw Right; Outfield) has to be one of the best examples of how life sometimes arms certain people with talents that could take them in several varied directions, but all the while, these opportunities are rising and falling constantly with how the individual makes and uses the decisions he or she finally decides to take responsibility for putting into motion.

Aaron Pointer (Batted Right/Threw Right; Outfield) has to be one of the best examples of how life sometimes arms certain people with talents that could take them in several varied directions, but all the while, these opportunities are rising and falling constantly with how the individual makes and uses the decisions he or she finally decides to take responsibility for putting into motion. Aaron Pointer batted .402 in 93 games for Salisbury (132 hit for 329 at bats) in 1961 for 19 doubles, 14 triples, and 7 home runs. By breaking the /400 mark, Pointer became the last professional baseball player to exceed that magic mark over a full summer of play. (Rookie League and Mexican League marks are not considered as data on this achievement trail.) At season’s end, Pointer was called up to the 1961 AAA Houston Buffs in time to also hit .375 ( 3 for 8 ) in four games.

Aaron Pointer batted .402 in 93 games for Salisbury (132 hit for 329 at bats) in 1961 for 19 doubles, 14 triples, and 7 home runs. By breaking the /400 mark, Pointer became the last professional baseball player to exceed that magic mark over a full summer of play. (Rookie League and Mexican League marks are not considered as data on this achievement trail.) At season’s end, Pointer was called up to the 1961 AAA Houston Buffs in time to also hit .375 ( 3 for 8 ) in four games.

When Cecil Cooper was named manager of the Houston Astros in late 2007, the fact that he’s black was not covered by the current media as even an interesting footnote to the fact that it then had been a little more than fifty-three years since Houston saw it’s first black baseball player take the field to play for a racially integrated Houston sports team. – Think about it. From the time Houston “welcomed” it’s first black baseball player to the time it saw its first black manager in baseball, fifty-three years and three months had passed.

When Cecil Cooper was named manager of the Houston Astros in late 2007, the fact that he’s black was not covered by the current media as even an interesting footnote to the fact that it then had been a little more than fifty-three years since Houston saw it’s first black baseball player take the field to play for a racially integrated Houston sports team. – Think about it. From the time Houston “welcomed” it’s first black baseball player to the time it saw its first black manager in baseball, fifty-three years and three months had passed. fact that I had just started to drive by that time and needed a good excuse to borrow the family car also factored into the equation. When I borrowed the car, I told my dad why I needed to be there at the ballpark that night. I wanted to see Bob Boyd play for the Buffs as the man who broke the color line in Houston.

fact that I had just started to drive by that time and needed a good excuse to borrow the family car also factored into the equation. When I borrowed the car, I told my dad why I needed to be there at the ballpark that night. I wanted to see Bob Boyd play for the Buffs as the man who broke the color line in Houston. 2007, the day that Cecil Cooper made his debut as a manager for the Houston Astros, a day for change, but it had nothing to do with race. Cecil just didn’t get here quite as loudly and, for reasons that have nothing to do with race, he also may leave soon, just as quietly, but maybe not. Maybe the Astros won’t unload all of the 2009 Astros’ failures on the back of their skipper.

2007, the day that Cecil Cooper made his debut as a manager for the Houston Astros, a day for change, but it had nothing to do with race. Cecil just didn’t get here quite as loudly and, for reasons that have nothing to do with race, he also may leave soon, just as quietly, but maybe not. Maybe the Astros won’t unload all of the 2009 Astros’ failures on the back of their skipper. Following his far better than average baseball career, Bob Boyd returned to his home in Wichita, Kansas, where he worked without complaint as a bus driver until he reached retirement age. Bob died in Wichita at age 84 on September 27, 2004. Today, the man who started his career with the Memphis Red Sox (1947-49) of the Negro Leagues is honored as a member of the Negro League Hall of Fame and also the National Baseball Congress Hall of Fame. Hopefully, we shall always continue to remember and honor Bob Boyd and all others who took the first step toward changing things that needed to change. Bob Boyd did his job with grace, dignity, and tremendously unignorable ability.

Following his far better than average baseball career, Bob Boyd returned to his home in Wichita, Kansas, where he worked without complaint as a bus driver until he reached retirement age. Bob died in Wichita at age 84 on September 27, 2004. Today, the man who started his career with the Memphis Red Sox (1947-49) of the Negro Leagues is honored as a member of the Negro League Hall of Fame and also the National Baseball Congress Hall of Fame. Hopefully, we shall always continue to remember and honor Bob Boyd and all others who took the first step toward changing things that needed to change. Bob Boyd did his job with grace, dignity, and tremendously unignorable ability.

The goal of every young and upcoming Houston Buff from 1923 through 1958 was to play well enough in the Texas League to either move up the following season to AAA ball, or even better, to do so well that that they went straight on up to the roster of the St. Louis Cardinals. I’m bracketing the era as 1923 through 1958 for one simple reason: That’s the time period in Buffs history in which the Cardinals either controlled or owned the futures of all ballplayers who passed through Houston professional baseball.

The goal of every young and upcoming Houston Buff from 1923 through 1958 was to play well enough in the Texas League to either move up the following season to AAA ball, or even better, to do so well that that they went straight on up to the roster of the St. Louis Cardinals. I’m bracketing the era as 1923 through 1958 for one simple reason: That’s the time period in Buffs history in which the Cardinals either controlled or owned the futures of all ballplayers who passed through Houston professional baseball.

The third man, Russell Rac, never got a single time at bat in the big leagues in spite of some pretty good hitting and fielding success with the Buffs in seven of his eleven season (1948-58) all minor league career. He began in Houston in 1948 – and he left as a Buff ten years later with a .312 season average, 12 homers, and 71 runs batted in for 1958. Few, if any, other players spent as many seasons as an active member of the Houston Buffs roster. Russell Rac went back to Galveston and into business from baseball following the 1958 season, where he continues to live in retirement as a man whose heart still belongs to baseball.

The third man, Russell Rac, never got a single time at bat in the big leagues in spite of some pretty good hitting and fielding success with the Buffs in seven of his eleven season (1948-58) all minor league career. He began in Houston in 1948 – and he left as a Buff ten years later with a .312 season average, 12 homers, and 71 runs batted in for 1958. Few, if any, other players spent as many seasons as an active member of the Houston Buffs roster. Russell Rac went back to Galveston and into business from baseball following the 1958 season, where he continues to live in retirement as a man whose heart still belongs to baseball.

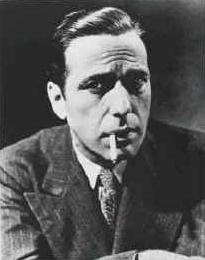

I grew up in a Post World War II era of blue smokey haze. Everything I saw, heard, or breathed vicariously into my lungs from the adults in my life said to me: “Smoking is good! As soon as you’re old enough you’ll be able to light up too!” My dad smoked, but so did most of the other dads and quite a few of the moms in our Pecan Park neighborhood in Houston. At Sunday Mass, it was like a stampede at the end as 75 to 100 men herded toward the front door for a post-spiritual firing up of the old Chesterfield and Camel nicotine incense out front. Hallelujah! None of those mamby-pamby filtered cigarettes were strong enough for my dad’s generation. These were real men who smoked only those short full-tobacco blast sticks fromthe “Big C” companies. And why not? “Seven out of ten doctors preferred and recommended Camels for your smoking pleasure!”

I grew up in a Post World War II era of blue smokey haze. Everything I saw, heard, or breathed vicariously into my lungs from the adults in my life said to me: “Smoking is good! As soon as you’re old enough you’ll be able to light up too!” My dad smoked, but so did most of the other dads and quite a few of the moms in our Pecan Park neighborhood in Houston. At Sunday Mass, it was like a stampede at the end as 75 to 100 men herded toward the front door for a post-spiritual firing up of the old Chesterfield and Camel nicotine incense out front. Hallelujah! None of those mamby-pamby filtered cigarettes were strong enough for my dad’s generation. These were real men who smoked only those short full-tobacco blast sticks fromthe “Big C” companies. And why not? “Seven out of ten doctors preferred and recommended Camels for your smoking pleasure!”